India rejects Beijing’s move, which seems aimed at bolstering its claims to disputed territory.

By Tenzin Pema for RFA Tibetan

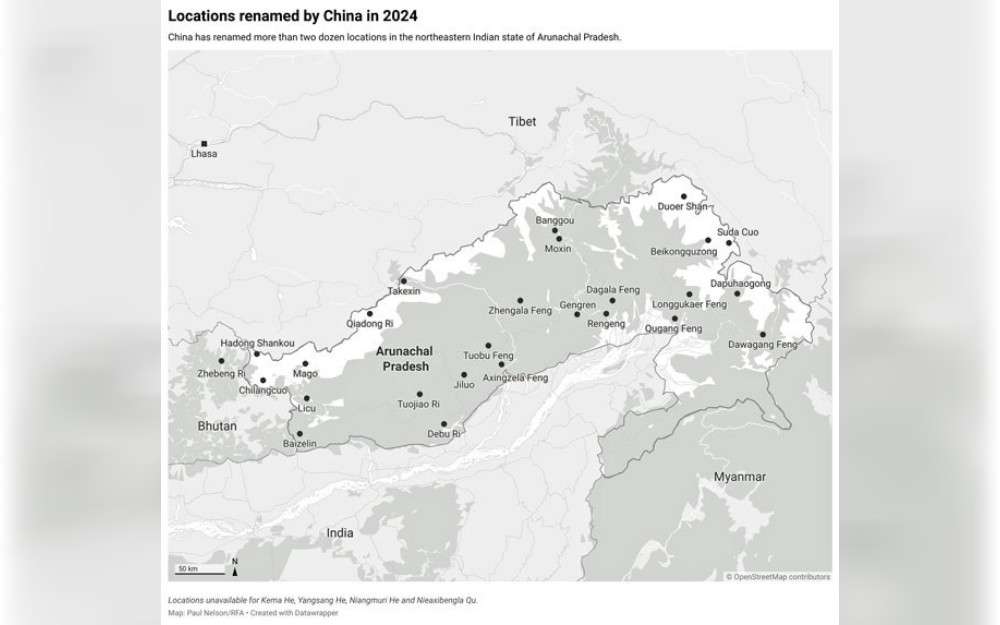

Beijing has issued Chinese names for 30 locations in Arunachal Pradesh to bolster its claims on the territory that is controlled by India, which quickly dismissed the move as meaningless.

It was the fourth time since 2017 that China released place names for geographical locations in what it refers to as Zangnan and claims is part of southern Tibet, in Chinese territory.

“If today, I change the name of your house, will it become mine?” asked India’s External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar on the sidelines of an event in the western state of Gujarat earlier this week.

“Arunachal Pradesh is a state of India,” he said. “It was, is, and will continue to remain a state of India. Changing the name of [various places] does not amount to anything.”

Tensions between India and China have escalated in recent weeks after Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to Arunachal Pradesh on March 9, prompting China to lodge a diplomatic protest.

The list issued by China’s Ministry of Civil Affairs includes standardized names for at least 11 residential areas, four rivers and 12 mountains among geographical locations in Arunachal Pradesh.

“In accordance with the relevant regulations on place name management of the State Council, our Ministry, together with relevant departments, has standardized some place names in southern Tibet,” the Chinese Ministry of Civil Affairs said in its official announcement. “The fourth batch of additional publicly used place names in southern Tibet is now officially announced.”

‘Cartographic aggression’

Experts said China’s attempts to rename places along its borders on all sides as well as in Tibet and other parts of China reflect its appetite for territorial acquisition and efforts to normalize its occupation of disputed territory.

“A big part of China’s cartographic aggression is renaming territories it sees as disputed,” said Sriparna Pathak, associate professor of China studies at the O.P. Jindal Global University in Haryana, India, and a former consultant at India’s foreign ministry.

China released the first such list of standardized names for six places in 2017, followed by a second list in 2021 with new names for 15 places, and a third list in 2023 with a list of 11 places.

China believes that it can continue to repeat that India’s territory is its own by assigning names to every small village, hill and water body in the region, in Chinese characters and Pinyin, said Anushka Saxena, a research analyst in the Indo-Pacific Studies Program at Bengaluru, India-based Takshashila Institution.

The move “is an exercise in rewriting history,” Saxena said. “With continued reiterating, it hopes that the nomenclature will slowly seep into how countries and officials refer to these areas.”

Few Western leaders understand that the Chinese Communist Party is angling to expand China’s borders on all sides – including in the South China Sea, said Michael Sobolik, senior fellow in Indo-Pacific Studies at the Washington-based American Foreign Policy Council.

China’s renaming of Tibet

It is using the same strategy in Tibet, experts said.

Last year, China replaced the use of the term “Tibet” with “Xizang” as the Romanized Chinese name on official diplomatic documents. Chinese media and the official account of the United Front Work Department’s “United Front News” said in October 2023 that “there is no more Tibet in the official documents of the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs.”

The commonly used name of Tibet by the international community encompassed not just Tibet alone, but also Tibetan-populated areas of Qinghai, Sichuan, Gansu, and Yunnan provinces, according to Chinese media reports. This geographical scope is consistent with the “Greater Tibet” defined by the 14th Dalai Lama, the exiled spiritual leader of Tibet.

China started using the term ‘Xizang’ to normalize its narrative that Tibet was never independent and was always part of China, Pathak said.

“The moment the term ‘Xizang’ gets normalized, what also gets normalized is India’s Arunachal Pradesh as ‘Zangnan’ or Southern Tibet as China sees it,” she said.

In an interview with RFA Tibetan in October, Sikyong Penpa Tsering, the elected political leader of the Central Tibetan Administration — the Tibetan government-in-exile in Dharamsala, India — urged the international community to reject the Tibet name change and “not to compromise with the CCP’s efforts to reshape history.”

Analysts also note the increasing frequency and speed of the issuing of such renaming of disputed territories.

The 2017 notification followed the Dalai Lama’s visit to Arunachal, while the 2021 announcement followed the border clashes in Tawang, a town in the state, Saxena added.

The 2023 notification was issued in April that year after a series of negative developments in India-China relations, including a visa spat over Indian journalists staying in China and an announcement that India would surpass China as the most populous country, Saxena said.

Additional reporting by Nyima Namseling, Nordon and Rigdhen Dolma. Edited by Malcolm Foster And Roseanne Gerin.

“Copyright © 1998-2023, RFA.

Used with the permission of Radio Free Asia,

2025 M St. NW, Suite 300, Washington, D.C. 20036.

https://www.rfa.org.”