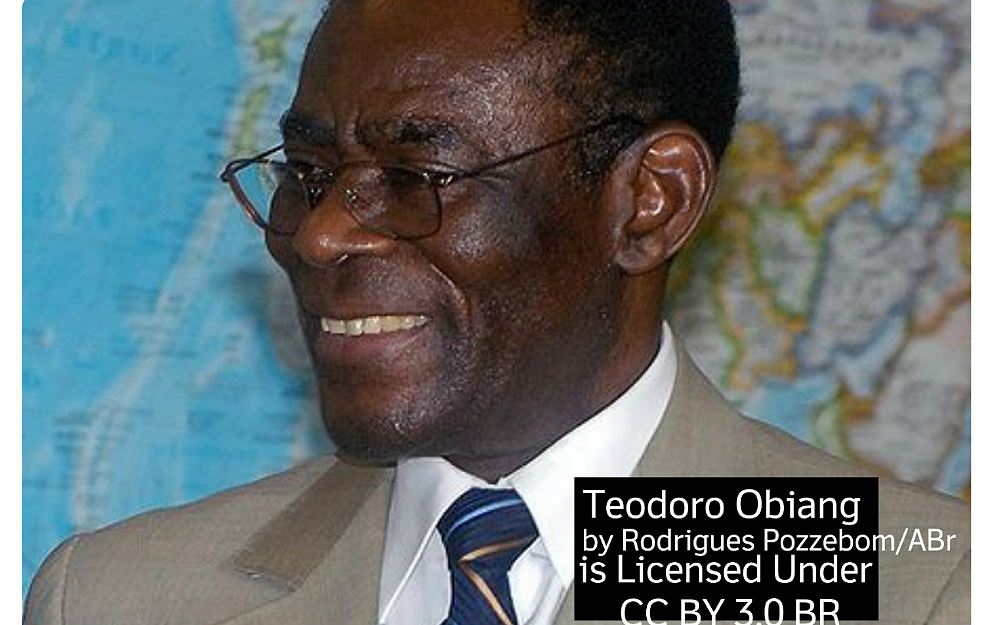

Authorities in Equatorial Guinea must halt decades of human rights violations and abuses including torture, arbitrary detentions and unlawful killings, Amnesty International said today, 40 years after President Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo seized power.

Equatorial Guineans who turn 40 this year were born, and grew up, in a country where human rights have been constantly and systematically violated. For too long, people have lived in a climate of fear because of impunity over human rights violations and abuses including the jailing of human rights defenders, activists and political opponents on trumped up charges,” said Marta Colomer, Amnesty International’s West Africa Senior Campaigner.

He said, “There have been glimpses of hope, like the 2006 law forbidding torture and President’ Nguema’s recent announcement of a draft law to abolish the death penalty. However, unless his government takes meaningful steps to enforce the law, fully respect human rights and end repression, the number of victims of human rights violations in Equatorial Guinea will continue to grow. This must stop”.

On 14 April 2019, President Nguema announced his intention to submit to parliament a bill to abolish the death penalty in Equatorial Guinea where the last recorded executions occurred in January 2014.

President Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasago took power on 3 August 1979 following a coup against President Francisco Masie Nguema. Since then, he has presided over an alarming decline in human rights, including torture, extra judicial executions, arbitrary arrests, and persecution of political activists and human rights defenders, which have been well documented by Amnesty International over the years.

In September 2006, parliament approved a law forbidding torture, which came into force in November of that year, but police regularly continue to torture on detainees to extract confessions. Many of these cases involve opposition members and political activists. Among them is Joaquín Elo Ayeto, an activist and member of the opposition party Convergence for Social Democracy who is currently in detention. He was arrested on 25 February this year at his house in Malabo and taken to the Central Police station. He was beaten severely while at the police station and hung up by his hands. Police wanted him to confess to an alleged plot to kill the president.

Some egregious cases of torture documented by Amnesty International took place between 1988 and 2009. These include 10 members of the People’s Union (Unión Popular) political party who were arrested and tortured in Bata and Malabo police stations in February and March 2009.

One detainee told the investigating magistrate that on one occasion he was tied up on the floor and offered money to “confess”. On another occasion, the police stuffed paper in his mouth, put him in a sack which was then tied and suspended and beat him. Although the detainee named those who reportedly tortured him, there was no investigation, and no one was brought to justice.

Amnesty International also documented the torture of 15 prisoners who were released after their sentences were reduced in a clemency measure in August 1988. Among them was prisoner of conscience Primo Jose Esono Mikali, who had his arms and legs tied together behind him, causing his back to arch painfully. Suspended from the ceiling by a rope, he temporarily lost use of his limbs.

The other prisoners were subjected to similar forms of torture, sometimes with a heavy stone placed on their arched back. Prisoners also described being hung by the feet and having their heads immersed in a bucket of dirty water, partially suffocating them, as well as being tortured with electric shocks.

Torture was also inflicted on members of the Bubi ethnic group, the indigenous population of Bioko Island in the northern most part of Equatorial Guinea. In 1998, many Bubi were tortured to extract confessions following their arrest after they launched several attacks on military barracks in which three soldiers and several civilians were killed.

Amnesty International documented cases of people being interrogated while suspended from the ceiling with their hands and feet bound together. Some people were also tortured at the time of their arrest in reprisal for the attacks. Many others were beaten with rifles, kicked and punched and some had part of their ears severed with razor blades and bayonets.

Bubi women were also publicly humiliated in the courtyard of the police station in Malabo. Some were forced to swim naked in the mud in front of other detainees and others were sexually abused. At least six detainees reportedly died after being tortured.

Executions under President Nguema started a month after the coup that brought him to power and have continued, with soldiers and police reportedly carrying out extrajudicial executions.

Death sentences were handed down to seven men, including former President Masie Nguema on 29 September 1979. Less than five hours later they were all executed by firing squad.

On 14 May 2012, a detainee, Blas Engó, was shot at close range by a soldier outside Bata prison as he tried to escape with 46 others during the night. In the same month, a military officer in Bata shot dead Oumar Koné, a Malian national, for refusing to pay a bribe at a road block.

In January 2014, nine men convicted of murder were executed, 13 days before a temporary moratorium on the death penalty was established.

Even children have not been spared

On 5 February 2015, dozens of children were among 300 youths arbitrarily arrested and beaten following protests during the African Cup of Nations in Malabo. The majority were arrested in their homes at night, or in streets far from the football stadium.

They were taken to Malabo Central Police Station, where they received 20 to 30 lashes each, and held in overcrowded and poorly ventilated cells occupied by adult criminal suspects. Some detainees were released after their families paid bribes to the police. On 13 February, the detainees appeared in court and all were released without charges.

More recently, in February 2019, Amnesty International highlighted the authorities’ failure to respect and implement the commitments they had made to ensure the right of human rights defenders, activists and journalists to work in an environment free from intimidation, harassment, violence and arbitrary arrests.

The authorities on 5 July issued a decree calling for the dissolution of the Center for Development Studies and Initiatives (CEID). The 40 years of President Nguema in power have also been characterized by a lack of independence of the judiciary. During all those years many critics and human rights defenders faced unfair trials.

One hundred and twelve people were convicted during a mass trial that took place in the city of Bata for an alleged coup attempt in December 2017. The conviction was full of procedural irregularities and rulings against the defense.

Despite a court ruling calling for his immediate release since April this year Bertin Koovi, a political opponent and activist from Benin continues to be kept in detention by the police in the city of Bata.

“For decades, President Nguema’s muzzling of dissent has had a devastating and chilling effect on human rights defenders, journalists and political activists. They have been persistently targeted solely for exercising their right to freedom of expression, peaceful assembly and association,” said Marta Colomer.

According to Marta, “It is time for President Nguema to close this gruesome chapter of his government’s human rights record and usher in a new era where human rights are fully and effectively respected, protected, promoted and fulfilled.”

You know Independent Journalism needs fund to run the not for profit venture Please contribute if you like our effort Donate through PayPal Or paytm +919903783187 phone pe +919875416249 Google Pay +919875416249 or write to us editor@crimeandmoreworld.com