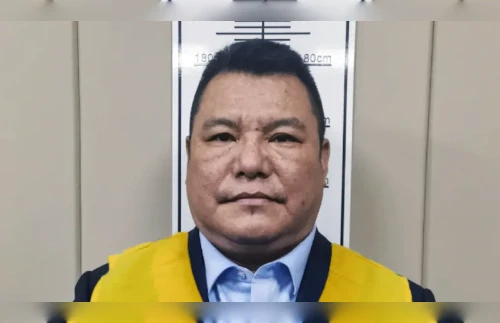

Chow Man-chung speaks about his new life in exile after his family fled an ongoing crackdown on dissent.

By Lu Xi and Raymond Chung

One year after the U.K. launched a visa scheme allowing millions of Hongkongers and their families to emigrate to the country amid Beijing’ ongoing crackdown on freedom of speech and political activism, tens of thousands have already made the move, many of them hoping for a better life for their children.

The scheme saw nearly 90,000 applicants in its first eight months, with long lines at airport check-ins and tearful scenes of farewell showing just how many were willing to start over, rather than tolerate life under the national security law, with no meaningful vote, and with ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP) propaganda increasingly finding its way into their children’s education.

Under the scheme, holders of the British National Overseas (BNO) passport, once derided as a useful wedge for a wobbly table or a doorstop, are allowed to live and work in the U.K., with a pathway for eventual citizenship.

Journalist Chow Man-chung, 46, says he had doubts as soon as the new law was imposed on Hong Kong by the CCP.

“When I heard that the common law presumption of innocence would be reversed under the national security law, something I had known since childhood, I wondered if it was still going to be safe for me [in Hong Kong],” Chow told RFA.

“I thought it would have a negative impact on my kid’s development, and on how he sees the world, if there were so many red lines [forbidden topics],” he said. “I thought that would be very unhealthy.”

Chow said the danger was that even adults were at risk of becoming passive in the face of CCP propaganda or injustice, and “anesthetizing themselves.”

Chow said his elderly mother had also told him to take the kids overseas, despite the fact that she plans to stay on in Hong Kong.

“I had to use words the kids were able to understand when I explained to them why we were going to live somewhere else, because I had to prepare them psychologically to not see the kids and relatives they had grown up with for a while,” he said.

Roller-coaster ride

Emotionally, the transition has been a roller-coaster ride, but politically, Chow said, he was past the point of no return.

Shortly before they left Hong Kong, photos of the Chow family waiting patiently outside a cordoned-off Victoria Park on the anniversary of the 1989 Tiananmen massacre made Hong Kong media reports. Chow has the photo on the cover of a carefully crafted photo album carrying the family’s most cherished memories of their home city.

For Chow, the pain of parting from friends, and from his home, is still raw.

“The plane took off to the northeast that day, turned around Disneyland, then banked across the south of Lamma Island, then turned around and headed north, as if you we were going on a last tour of the city,” he said, his voice choked with emotion at the memory.

What awaited the family was a culture shock, not least because they could no longer afford to pay someone to help out in the home, and Chow taking care of daily tasks including school run, housework and homework supervision.

While driving, he would listen to Hong Kong radio stations to remind him of home, including music by homegrown rockers the Rubber Band.

Chow doesn’t expect his kids to share his intense sense of nostalgia or exile from Hong Kong, but he hopes they will understand, as they adapt to their new lives in Kingston, southwest London.

“I think there is a large number of Hongkongers here — sometimes when you ask a question [on group chat] and get a lot of responses, you don’t feel so alone,” he said.

“We may feel that we just fell through a black hole, that … we are to be pitied, that there is so much we don’t know … but there are a lot of other people just like you,” Chow said.

One in five want to emigrate

Chow has continued with his activism in London, printed fliers for a recent protest against Hong Kong’s vanishing press freedom. Many of his colleagues have been arrested under the national security law, or made unemployed as one after another pro-democracy media outlets relocates or folds.

He described the BNO visa scheme as a “small window” in time and space.

“That window was so small, and we were in just the right place to be able to walk through it towards the light, towards the exit,” Chow said.

A poll by the Hong Kong Democratic Party in December 2021 found that 58 percent of people are unhappy living in the city now, and 22 percent are planning to emigrate.

On the democratic island of Taiwan, an official report said it had also received more than 2,000 calls to its one-stop immigration service for Hongkongers hoping to relocate to Taiwan amid the national security crackdown.

Enquiries were relating mostly to investment visas, routes to settlement, spousal visas, employement and schooling, but mostly routes to long-term settlement, the Mainland Affairs Council (MAC) said in a recent report on the status of Hong Kong.

Translated and edited by Luisetta Mudie.

Copyright © 1998-2020, RFA. Used with the permission of Radio Free Asia, 2025 M St. NW, Suite 300, Washington DC 20036. https://www.rfa.org