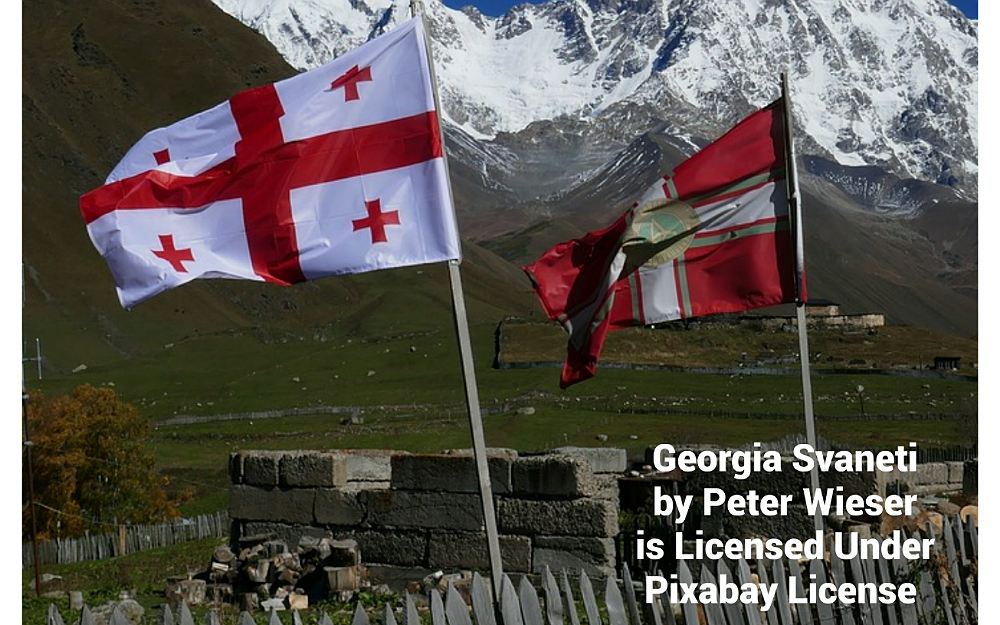

From openhanded hospitality to fierce blood feuds, centuries-old customs are fading in Svaneti as the remote Caucasus highland becomes a trendy tourism destination.

By Giorgi Lomsadze/Eurasianet

The Towers

The village of Lenjeri is an Escher maze of medieval towers, ancient ruins and eligible bachelors. Twenty young local men are in need of wives, says schoolteacher Lali Khaptani as she leads the way to her house.

“Be warned that after you set your foot in my house and break bread with me, we become a family, like it or not,” Khaptani says. These are the old ways of hospitality, once sacrosanct in Georgia’s highland region of Svaneti.

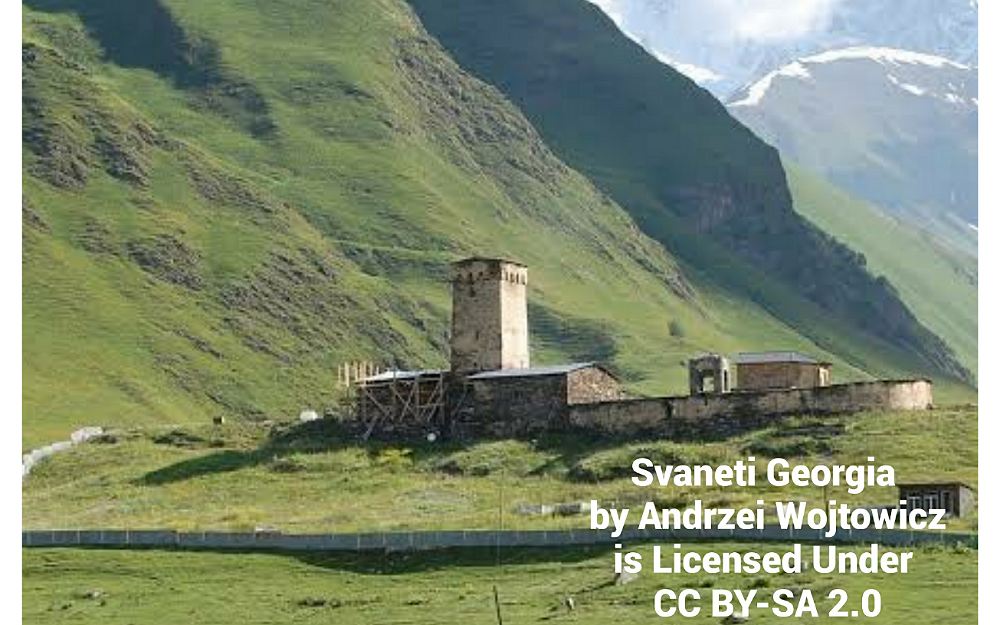

Her sun-dappled garden is shaded by a massive walnut tree and several stately stone towers – across Svaneti clusters of these towers, with soaring peaks in the background, combine to create astounding visual spectacles. Every family home had its own towers to defend against invaders – feudal barons, foreign armies and government officials – leaving the region largely free of external rule.

These days, the towers serve as an attraction for invaders of a different kind: armies of tourists. Travelers from America to China and everywhere in between lay siege to the hamlets of Svaneti. Hotels and guesthouses now pack a place that most Georgians, let alone foreigners, until recently gave a wide berth, deeming it unsafe and inaccessible.

The boom is changing the way of life in Svaneti. As the highland succumbs to capitalism, the Svans have learned to monetize their mountains and culture. Khaptani laments that hospitality, their second nature for centuries, has become an industry.

“We used to say ‘How are you?’ as a way of greeting, now they say ‘How many?’ as in how many customers have you had today,” she says, with a sting of distaste in her voice.

A mountain of pumpkins – one of few vegetable crops that do well at this altitude – is heaped up in the sunroom of her house. The dining room features solid, wooden furniture with traditional carvings and Khaptani’s artworks: local scenes crafted from wood shavings, tree moss and beads. “Oh, it is nothing, just a pastime,” Khaptani says demurely. “My niece insisted that I put it out here.”

She speaks graceful, lettered Georgian, pure of any loanword contamination prevalent in the cities down below. When addressing her family members, she occasionally drops a word or two in the Svan language, an endangered kin of Georgian.

“The Svan language is disappearing,” she says resignedly. “The more people come to Svaneti, the less there is use for Svan. Georgian and English is what everyone wants now.”

But there is also a bright side: people who had left Lenjeri to escape hardscrabble mountain life have come back now that there are economic opportunities in Svaneti. “It warms my heart to see people return, and we have tourism to thank for it,” Khaptani says.

One of the returnees is Khatpani’s own nephew, Khvicha, a sergeant in the Georgian army and now part of Lenjeri’s squad of bachelors.

“I built all of this with my own hands,” Khvicha says, pointing at a pair of snug wooden cabins in his yard and a wooden veranda abutting his family tower.

The 34-year-old fought against invading Russian troops in the 2008 war and later turned down an opportunity to serve in Iraq – the best-paid job in the Georgian military. He returned last year to his ancestral home to set up a guesthouse.

He briskly climbs the steep, shaky ladders to get to the crown of the tapered tower, crenelated with holes at its fourth, top floor. “From here they shot guns, from there they threw stones down,” he explains, pointing at the slits and loops in the walls.

The tour does not end there. Khvicha pushes open a hatch in the ceiling and pulls himself up with an acrobatic move to get on the wooden plank-covered roof. This correspondent, burdened with a camera bag and a sudden fit of acrophobia, follows suit and is treated to a dizzying view.

The surrounding mountains loom close, their steep, woody slopes emblazoned with fall colors: golden, scarlet, lawn-green, with the conifers providing accents of dark green. Sky-scraping glaciers lord it over the entire landscape.

It’s a palm-sweating experience to balance on the slanting, shaky roof that barely has space for two, yet Khvicha thinks it is as a good a place as any for the interview. He says he wants his guesthouse to strike a balance between business and tradition: “I want my guests to see how we live, share a meal with us, go check the animals in the barn.”

The Dark Image

In a flickering, black-and-white sequence, a pregnant woman stands on top of a hill, desperately raising her hands in a cry for help. Men, slathered in dirt and sweat, sway pickaxes and grind rocks. This is the climactic moment in Georgia’s 1930 Jim Shvante (Salt to Svaneti), which depicts the struggle to build a proper road to bring modernity (and with it, salt) to Svaneti.

The film limned the Svans’ life in isolation and abject poverty, tormented by the unforgiving climate, back-breaking labor and their own austere traditions. That dark, haunting image stuck to the region for the rest of the 20th century.

The image is very different today. In 2019, Svaneti is a tourist mecca, resplendent with colors and cacophonous with languages from around the world. Selfies are snapped, trails are hiked and alcohol pours in Mestia, the central town enclaved by woody mountains, alpine slopes and icy peaks.

Best of luck to anyone trying to get on the tiny, perennially sold-out planes that buzz in and out of Mestia. A visitor’s best bet to get to Svaneti is instead by car up the hairpin, though recently improved, road from the lowlands along the Black Sea.

The road burrows through tunnels and crawls under menacingly cantilevered cliffs to reach the region’s largest town of Mestia, at 1,500 meters (almost 5,000 feet) above sea level. There, cab drivers-cum-tour guides compete to take visitors a further 600 meters in altitude up to the region’s showcase, UNESCO-protected village, Ushguli.

Before, when we saw someone come to Svaneti, all we thought about was how to entertain our guests, to invite them into our houses, to show them around. Now when we see visitors, all we think about is how much we should charge them,” says one cab driver with a guilty smile as he maneuvers his Pajero SUV up to Ushguli, a two-hour drive (or a four-day hike) from Mestia.

Japanese Delica vans, the wheels of choice in Svaneti, unload groups of Saudi, Israeli andq Russian travelers in Ushguli, where a stockade of towers and houses is perched above the tree line, at the foot of a massive glacier. Hikers – Polish, Norwegian, French – plod their way further up and get rewarded with a close-up of Shkhara, Georgia’s highest peak and the third tallest in the Caucasus. One of Europe’s highest settlements, Ushguli was the setting of Jim Shvante.

The Mountain Law

Khvicha leaned over the edge of the roof pointing at the village below, with its warren of close-knit households and a scarce choice of brides. “Most of us in this or neighboring villages are related to each other in one way or another, that’s why so many of us can’t get married,” he says with a laugh.

Many Svans prefer to marry fellow Svans, but the recent openness has brought growing exogamy. A landlady in Mestia quips that “the globalization” came into her house in the form of a daughter-in-law from Kakheti, a wine country in the opposite corner of Georgia.

Bride-napping was common in the not-too-distant past. “A Svan will kidnap you for a bride and put you in his tower,” daughters were told down in the valleys below Svaneti. “Many of my older relatives were actually kidnapped by their husbands,” says Nino Gudashvili, a Svaneti-native teaching English in the capital, Tbilisi. “Some of it was staged: couples would in fact elope under the guise of kidnapping, but real kidnappings happened, too.”

The highland preserved its clan rule and its mix of Christian and pagan rites as empires rose and fell in the lowlands below. Community elders, or makhvshis, acted as law enforcers, mediators and judges. They still do, to a degree.

“The most respected individuals are elected as makhvshis and they take a sacred oath to serve their communities. The title is not inheritable,” Khaptani says. “It is a perfectly democratic arrangement.”

Svan law still often takes precedence over national law. If a Svan kills a fellow Svan, even if he serves a prison sentence for it, the blood debt owed to the victim’s family is not considered paid until makhsvhis, selected by both sides, negotiate a settlement.

“I grew up with the belief that if someone hurts me or my family member, I have to hurt them back in kind,” Gudashvili says. “Had someone killed, say, my sibling, I had to kill the killer – police and all that was not an option.”

Gudashvili grew up in the 1990s, when Georgia, newly independent from the Soviet Union, plunged into economic crisis and civil unrest. Armed robbery, never unheard of in Svaneti, became rampant. “Everyone had guns. Boys would get drunk, pull out automatic rifles and start shooting,” Gudashvili says. “When you are young, drunk and a holding an automatic rifle, chances are the bullet will hit someone.”

Former president Mikhail Saakashvili, who modernized Georgia with a strong arm, oversaw a crackdown on Svaneti’s most recalcitrant clans in the 2000s. Many arrests were made and guns confiscated. A new police station was established in Mestia as an emblem of the changing times.

Mestia was spruced up and a new road shortened the trip there by several hours. The first ski lift opened late in 2010 as Saakashvili vowed to turn Svaneti into “the Switzerland of the Caucasus.”

Switzerland with an edge

It’s come pretty close. In winter, skiers and snowboarders, especially off-piste enthusiasts, raise clouds of powder on the dramatic slopes above Mestia. But it’s summer when Svaneti gets really busy.

International travel magazines and guides churn out gushing accounts – hiking in Svaneti “will make you wonder why you bothered with Alps,” the Guardian wrote – and the legend of Svaneti has spread through word of mouth, as well. In Mestia, two women, an American and a Peruvian, say they didn’t know about Georgia – let alone Svaneti – until they heard fellow hikers rave about it in the French Alps.

Many hikers come for theTranscaucasian Trail, a project to connect all of the South Caucasus through a web of hiking paths. “The trails attracted a lot of English-speaking people to Svaneti, as we have a website in English and it has been in the news, but there are people from everywhere, so I’m not going to take credit for it – or blame,” says Paul Stephens, an American who is managing the creation of the trail, with a laugh.

Once a Peace Corps volunteer in Georgia in the mid-to-late 2000s, Stephens ended up spending much of his time in Svaneti and has experienced the changes first-hand. “You used to show up in a Svan village and have a mountain of food laid in front of you … but now you have thousands coming to Svaneti,” he says. “It is perhaps sad that you can’t experience the moment of genuine hospitality anymore, but tourism was inevitable in Svaneti – it is a beautiful place with incredible natural and cultural heritage. People will come as long as it is safe.”

The warrior spirit still manifests itself occasionally. Last year, when one local man could not get a seat for himself and his guests in one of Mestia’s restaurants, he shot a gun in the air to convey his displeasure with the service.

Farming, which still involves buffalo-drawn ploughs in some areas, is on the wane in Svaneti, as many households prefer (and can afford) to buy food. Gudashvili remembers the toils of coaxing an uncooperative cow to return from its mountain pasture and rolling hay down from the steep slopes. “The ball would get larger and larger, and harder to drag down,” she says.

Religious traditions remain strong. While opening guesthouses and learning English, Svans continue to practice their ancient rituals, a blend of pagan and Christian rites. An ancient harvest festival, Lamproba, long extinct in the rest of Georgia, is alive and well in Svaneti. Women make bread as votive offerings and men carry torches to churches, sacred sites and graveyards at night.

Gudashvili says that paying respects to their ancestors provides a sense of continuity of the Svan way of life. “At a dinner table, we turn around dishes and cups, symbolically offering the meal to the dead,” she says. “I guess it’s also a way to extend your life beyond death: when you do it, you are thinking that long after you are dead and many things have changed, someone will still turn a cup for you.”

(The Story Was Published by Eurasianet Eurasianet © 2019)

Escaping from Scam Center on Cambodia’s Bokor Mountain

UN Security Council Meets to Discuss Children and Armed Conflict

10 Shocking Revelations from Bangladesh Commission’s Report About Ex-PM Hasina-Linked Forced Disappearances

Migration Dynamics Shifting Due to New US Administration New Regional Laws

UN Security Council Meets to Discuss the Maintenance of International Peace and Security and Artificial Intelligence

Winter Brings New Challenges for Residents living in Ukraine’s Donetsk Region

Permanent Representative of Israel Briefs Press at UN Headquarters

Hospitals Overwhelmed in Vanuatu as Death and Damage Toll Mounts from Quake

If you want to contact us

For our latest updates

Subscribe our You Tube Channel

From our Archive