Award-winning author Muk Yu ‘wanted to take the time’ to understand Hong Kongers who now live in Taiwan.

By Jojo Man for RFA Cantonese

Hong Kong author Muk Yu never took part in the 2019 protest movement.

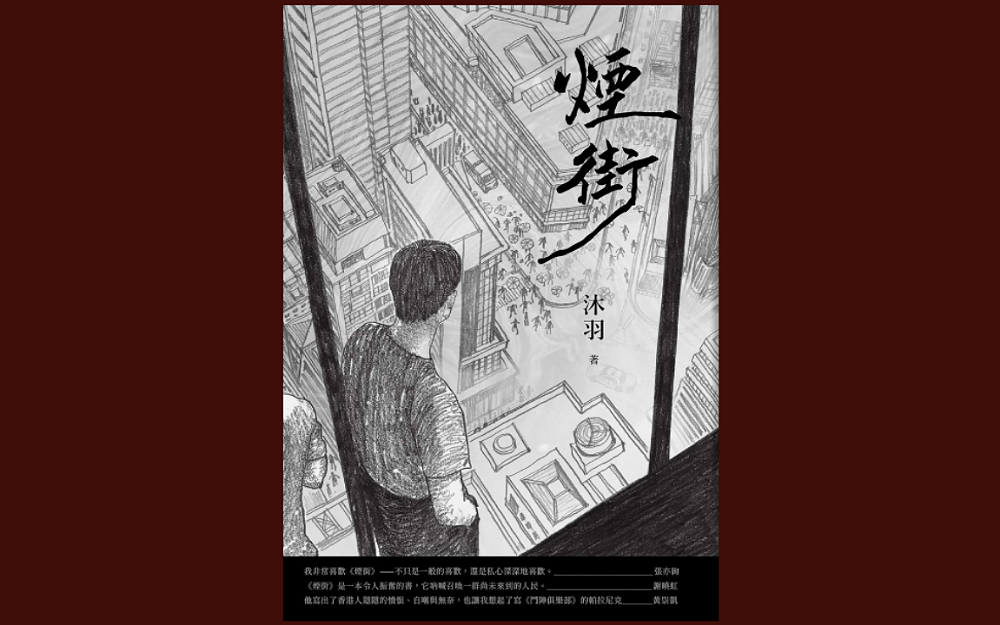

But his debut book of eight short stories — titled “Smoke on the Streets” — set in the aftermath of mass resistance to the ongoing erosion of the city’s freedoms under Communist Party rule has already garnered a literary award on the democratic island of Taiwan.

Muk won first prize in the fiction category at the 2023 Taipei International Book Exhibition Awards for the book, which the judges described as “a faithful portrait of Hong Kong in the post-protest era, its social issues, and the fear felt by Hong Kongers living in Taiwan.”

The bearded Muk is still in his 20s, yet is no stranger to the literary limelight. “Smoke on the Streets” also picked up an award at the 2022 Openbook creative awards, also in Taiwan.

A graduate of the creative writing program at Hong Kong’s Baptist University, Muk went to study literature at master’s level in Taiwan, but has only been writing for about four years, so describes himself as a “novice.”

“If they write well, Hong Kongers can actually gain recognition in Taiwan, and they can continue to stand up [for their city] here,” he said in a recent interview.

On the democratic island, which has never been ruled by the Chinese Communist Party, a writer doesn’t have to worry about putting themselves in danger because of what they write, Muk said.

“All they have to worry about is making their work better,” he said, adding: “I’ve always taken the no scruples approach.”

Dark humor

Muk likes dark humor that tramples the boundaries of what is acceptable for fiction-writing.

He finds irony in the fact that “Smoke on the Streets” isn’t on sale in Hong Kong, where a draconian national security law has banned public criticism of the government or “glorification” of the protest movement.

He claims that he’s not sure it has even been banned.

“If people can’t see it, I guess it must have been taken off the shelves due to poor sales,” Muk said with a smile, adding that readers in Taiwan should make the most of the opportunity they have to buy it.

Muk wrote the stories because he wasn’t in Hong Kong at the time of the protest movement, and wanted to make his own contribution, he said.

“If I were to write non-fiction or a work of theoretical criticism without being there on the ground, there would be a problem with the authenticity,” he said. “But with fiction, I was more concerned about exploiting the people who were there, and about writing … it badly.”

“More absurd than reality”

He said the actual events of the past few years in Hong Kong and beyond have given fiction a run for its money, however.

“If a novel were to set out to try to be more absurd than reality, then I don’t think it can win that fight, because Hong Kong is such a magical city,” Yuk said. “Was there anything more absurd than LeaveHomeSafe?” he said, in a reference to the COVID-19 vaccine passport and tracing app used after the pandemic hit the city in 2020.

“It would be hard to make up something as crazy as that,” Muk said, adding that he hoped to keep a sense of light-heartedness despite the events of recent years.

“It’s always a good thing to face these absurdities with a smile, because that’s how black humor works,” he said. “It’s always up to you how you choose to see the world.”

“If you take totalitarianism very seriously, then you will be left as a passive entity, but if you laugh in the face of unreasonable oppression, then totalitarianism has no hold over your emotions, and at that point, the power difference is reversed,” Muk said.

“Broken Cantonese”

Muk has already integrated somewhat into life in Taiwan, riding a scooter and marrying a local woman, and speaks his native Cantonese less fluently than he once did.

He jokes at the end of the book that he only speaks “broken Cantonese” now, a bitter little joke that won’t be lost on people who fear Hong Kong’s Cantonese culture may soon be a thing of the past under Communist Party rule.

He still stays in touch with Hong Kongers in Taiwan, although he feels that all of them have changed since they left the city, much as he has.

Many of the stories in “Smoke in the Streets” focus on this group, which Muk isn’t entirely sure he fully understands yet.

Many of them came to Taiwan for different reasons, and one story, titled “Cartography,” depicts the way in which they form their own immigrant culture in Taiwan. It also shows how disparate they are.

“I think Hong Kongers can be united when there is urgent need,” he said, citing the 2019 protests, the 2014 Umbrella Revolution and the “Fishball Revolution” 2016 civil unrest in Mong Kok.

At other times, not so much. They haven’t always felt the same way about their city, either, Muk said.

“Back in the 1990s [a researcher] asked the people of Hong Kong whether they liked their city, and most of them said they didn’t,” Muk said. “So when a group of people stood up and said they really liked it the way it was, that was a change.”

Muk said he has postponed the publication of his next book to better get to grips with Hong Kongers in the diaspora, something he feels “needs to be digested.”

“Now they’ve experienced really liking Hong Kong, and they have gone back to feeling differently again now,” he said. “I felt I hadn’t really understood their experience, so I wanted to take time to understand what the Hong Kongers in Taiwan are thinking.”

Translated by Luisetta Mudie. Edited by Malcolm Foster.

Copyright © 1998-2020, RFA. Used with the permission of Radio Free Asia, 2025 M St. NW, Suite 300, Washington DC 20036. https://www.rfa.org.