Nazmul Ahasan/Oakland,Calif.

A 12-hour gunfight and the torching of a refugee settlement along the Banglesh-Myanmar border thrust the Rohingya Solidarity Organization, an old armed insurgent group, back into the spotlight.

The fighting last month between members of RSO and the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) insurgents left at least one person dead and forced hundreds of Rohingya to flee the encampment.

The violence was the first known act of open fighting between the two militant groups, who both claim to support the Rohingya cause against the Myanmar military. It boiled over from tensions in a turf war in the sprawling refugee camps near the frontier between the neighboring countries.

BenarNews obtained eye-witness testimonies and photographs of the slain person, Hamid Ullah, that suggest he was wearing a camouflage uniform emblazoned with an RSO insignia.

Founded in 1982, the RSO was the foremost Rohingya armed group fighting the Myanmar military before it went into a prolonged hibernation in the 2010s. ARSA filled that vacuum when it carried out a series of attacks against Myanmar’s border outposts, starting in 2016. These provoked a Burmese military crackdown that unleashed a huge exodus of Rohingya refugees into Bangladesh in 2017.

But as ARSA’s image within the Rohingya community faltered, RSO made a comeback after the Myanmar military coup in February 2021. Since then, the groups have traded barbs, with each trying to establish dominance in the Rohingya camps, culminating in the violence that flared up at the refugee settlement in the no-man’s land between the two borders on Jan. 18.

“We could not be a silent spectator but were compelled to suppress that terrorist gang who were extensively carrying out different criminal activities […] in the Rohingya refugee camps [from] that zero-line camp,” the RSO said in a statement provided to BenarNews.

Efforts to reach ARSA were unsuccessful.

This screengrab from a video shows smoke in the distance from a fire at a Rohingya settlement in a no-man’s land between Bangladesh and Myanmar amid fighting between Rohingya insurgents group, Jan. 18, 2023. The community seen in the foreground is a village in Naikhongchhari, a sub-district of the southeastern Bangladeshi district of Bandarban.

ARSA burst onto the scene after it attacked Myanmar’s border outposts in 2016 and 2017. The Myanmar military used those attacks to justify its brutal counter-insurgent offensive in August 2017 that forced about 740,000 Rohingya to flee to Bangladesh.

The United Nations described the crackdown as “a textbook example of ethnic cleansing,” and the United States eventually declared the atrocities and other abuses carried out by the Burmese security forces during the offensive as genocide.

Following the February 2021 coup d’état in Myanmar, the RSO resurfaced in Bangladesh that March.

An official with Bangladesh’s National Security Intelligence claimed that despite its sudden re-emergence, RSO has been active in the Chittagong Hill Tracts area in the southeast, and in neighboring Cox’s Bazar where many refugees have sheltered since the 2017 military clearance operation.

“RSO is not like ARSA,” he told BenarNews. “[RSO members] are all highly trained.”

The official spoke on the condition of anonymity because he was unauthorized to speak to reporters.

The border settlement in the no-man’s land – also known as “Zero Point” – is outside the purview of either Bangladesh or Myanmar, which allows Rohingya militants or criminals to use it as a sanctuary, according to Christina Fink, a professor at Georgetown University who is an expert on Myanmar.

“The reason for the fighting is that these two Rohingya armed groups are competing to gain control over the camp, and that’s because of its location,” Fink told Radio Free Asia’s Burmese service.

“And whoever has control of this piece of land can more easily make forays into Myanmar. More importantly, they can make money by taxing informal border trade.”

The brief episode of recent fighting followed an extraordinary escalation between Bangladesh security forces and suspected ARSA members in the encampment along the border in November 2022.

At the time, the Rapid Action Battalion, an elite Bangladeshi police unit, conducted a raid against “drug smugglers,” during which an intelligence officer with the Directorate General of Forces Intelligence (DGFI) was killed. Although Bangladeshi authorities initially blamed unspecified “drug smugglers” for the incident, DGFI later formally accused ARSA chief Ataullah Abu Amar Jununi and others of killing its official.

The government also withdrew the RAB commander who conducted the raid, which appeared to have violated international norms for respecting no-man’s land areas.

Shafiur Rahman, a Britain-based journalist and an influential Rohingya watcher, connected the “botched” November operation with the recent RSO-ARSA skirmish.

“Bangladesh could not risk becoming implicated in the situation again,” he wrote in a recent blog post. “Therefore, it is not surprising that many residents of ‘no-man’s land’ believe that while the January 18th attack was carried out by RSO, it must have had the approval of those in power.”

Ko Ko Linn, an RSO spokesman, told BenarNews via WhatsApp, “We are very much thankful to the government and the people of Bangladesh for giving long-time shelter to our helpless community.”

“The government, the politicians, and the people are seeking goodness for our community. The government strongly stands for us with full sympathies,” he said.

Officials at Bangladesh’s foreign ministry did not immediately respond to a BenarNews request for comment about the country’s alleged backing of RSO.

Long hibernation

Throughout the 1980s and ’90s, the RSO operated in the border areas of Bangladesh. Independent observers credited the support of successive Bangladeshi governments for the RSO’s growth.

In 1991, Bertil Lintner, a Swedish journalist who extensively covered Myanmar militant groups, reported about the presence of heavy artillery in RSO camps inside Bangladesh.

In 1998, the group reportedly dissolved under an umbrella organization, the Arakan Rohingya National Organization.

Some observers claimed that RSO built a strong rapport with the Jamaat-e-Islami (JeI), a Bangladeshi Muslim political party, and also suggested that some Rohingya militants tied with RSO had links with the Taliban and al-Qaeda.

But in Bangladesh, its ties with JeI proved crucial.

Linter reported that an entity in Cox’s Bazar tied to a JeI-linked charity was RSO’s military headquarters and that JeI’s student cadres received training, too.

Bangladeshi media reports also suggest that RSO operatives easily blended into Cox’s Bazar’s local communities due to cultural similarities and helped build a robust political base in support of the JeI.

When Bangladesh’s Awami League party returned to power in 2009, RSO faced a severe crackdown, primarily because of its deep ties with JeI, and subsequently faded into obscurity.

Meanwhile, Myanmar never stopped blaming RSO for any Rohingya-related violence in its territories.

In October 2016, when Burmese border outposts first came under attack from what would later be known as ARSA, the Myanmar government initially blamed RSO. It took Myanmar some time to realize that ARSA and RSO were separate groups.

Filling the vacuum

In the years that followed the 2017 Burmese military offensive that drove nearly three-quarters of a million Rohingya into Bangladesh, ARSA built a solid base across Rohingya camps in Cox’s Bazar, where about a million refugees live.

An array of observers, including Tom Andrews, the U.N. special rapporteur for Myanmar, accused ARSA of operating a ruthless reign of terror in the Bangladeshi camps.

ARSA denied the allegations and insisted that criminals were abusing its popularity, but the organization’s denials now bear scant, if any, credibility.

For its part, the Bangladesh government for years steadfastly denied that ARSA rebels had a foothold in the crowded and sprawling camps near the Myanmar frontier.

The government may have been worried that an acknowledgment would undermine its pressure campaign against Myanmar to take back its nationals, according to observers.

But things started to change when the Myanmar military staged a coup in early 2021.

With the elected civilian government of Aung San Suu Kyi gone overnight, Bangladesh saw little hope for Rohingya repatriation under a junta.

Meanwhile, opposition groups in Myanmar formed an alternative government in exile, known as the National Unity Government (NUG).

Its armed wing, the “People’s Army,” aimed to unite Myanmar’s many rebel groups and factions divided across ethnic and political lines.

But even within Myanmar’s opposition factions, ARSA was deemed categorically unfit to join the People’s Army.

In that context, the RSO emerged from its prolonged hibernation in March 2021 when its social media pages popped up and published statements supporting the NUG.

Aung Kyaw Moe, the Rohingya Affairs advisor to the shadow National Unity Government (NUG), acknowledged the liaison with the RSO.

“After the revolution, we met the RSO online,” he told RFA Burmese. “They said they were contributing to the revolution, but they didn’t.”

Several claims by RSO of high-profile attacks against Myanmar military or border guards were discredited by observers.

“Like other Rohingya groups, RSO produces a lot of propaganda,” a long-time Western analyst, who was not authorized to speak to the media, told BenarNews.

“For example, in October last year, they claimed they had captured a Myanmar border guard post after a fight but it later turned out it was an abandoned post.”

Today, most Rohingyas see RSO as the lesser of the devils, while Rohingya diaspora figures publicly renounce ARSA.

“The Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army is considered a ‘terrorist group’ by the majority of Rohingya,” Ro Nay San Lwin, a Europe-based Rohingya activist, told RFA Burmese. “We clearly said that we cannot accept the ARSA. Can the RSO work in an orderly manner? We will see.”

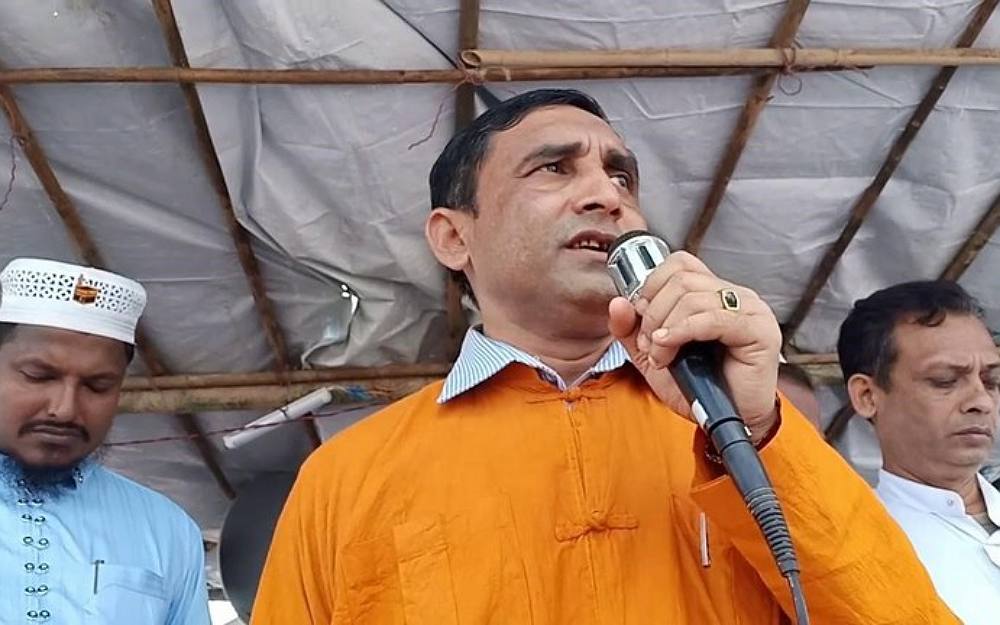

But it took the murder of Muhib Ullah, a famed Rohingya activist leader, in September 2021 for the Bangladesh government to crack down seriously against ARSA.

Muhib Ullah, a prominent civil society figure, had sought protection from the Bangladesh government after ARSA threatened him with death. After his murder at his office in one of the refugee camps, his family members publicly blamed the armed group.

A police investigation later found that ARSA killed him because of his popularity within the camp.

The murder put the Bangladesh government under enormous international pressure to improve safety and security in the camps. And as the government reshifted its focus on ARSA, other actors, including RSO, benefitted.

But to the ordinary Rohingya trapped in violence in the congested refugee camps, the armed resistance isn’t appealing.

“We face threats every day. You never know what will happen next,” Sayed Alam, a Rohingya living in the Kutupalong camp, told RFA Burmese. “But we have minimal interests in armed organizations. We are more interested in returning home to our own country and having our work back.”

Radio Free Asia, a news service affiliated with BenarNews, contributed to this report. Abdur Rahman and Ahammad Foyez for BenarNews contributed from Cox’s Bazar and Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Copyright ©2015-2022, BenarNews. Used with the permission of BenarNews.