Activists accuse Armenia’s new authorities of repeating the murky business practices of the government they ousted.

Ani Mejlumyan/Eurasianet

The revival of a controversial urban development project in central Yerevan has entangled the country’s post-revolutionary government in the kind of opaque deals, corruption accusations and property rights violations that were hallmarks of the former regime.

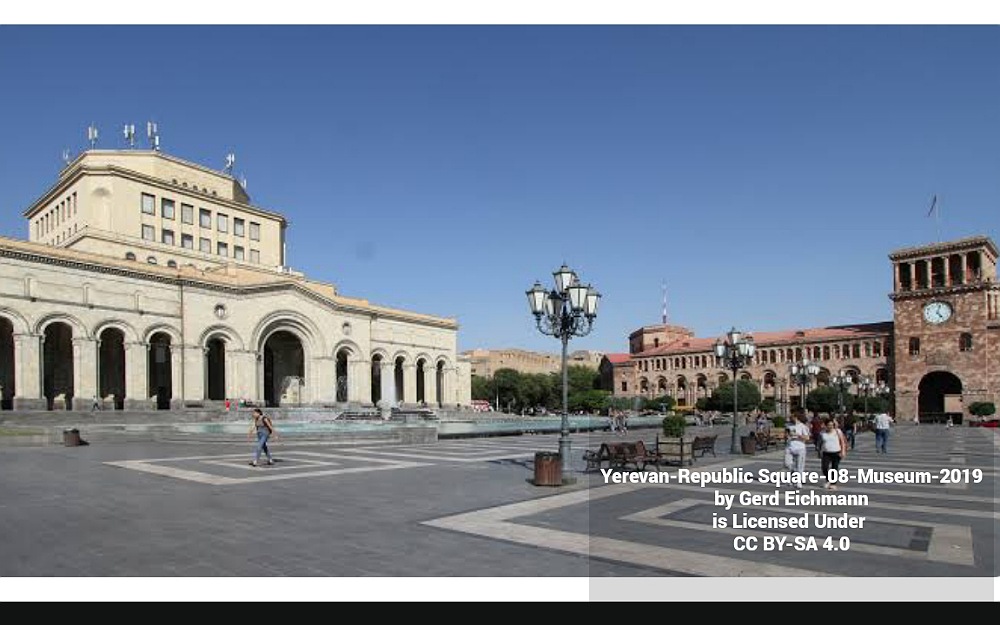

At issue is a neighborhood known as Firdowsi, from the main street that passes through it. It has long been in the sights of developers, given its central location just off Yerevan’s Republic Square. But the area also contains some of Yerevan’s relatively rare pre-Soviet architecture, as well as a community that calls it home.

The most recent plan to redevelop the area had appeared to lie dormant since a new government came into power on the back of the 2018 “Velvet Revolution.” But in June, a historic building in the neighborhood was torn down, signaling the resumption of the project.

“This project isn’t new, but we thought that the new government would have a different approach,” said Isabella Sargsyan, a human rights activist and a co-organizer of a civic initiative, Yerevan Heritage Protection Committee. “The trigger for us was when, during the state of emergency, they demolished a 19th-century building,” Sargsyan told Eurasianet.

The developer of the project, Dianar, got the contract under the old government, and civil society groups have criticized a number of non-transparent elements in the deal.

One of the shareholders of Dianar, Eduard Melikyan, was director and shareholder of another company, called Glendale Hills, that had also gotten a contract in 2008 to redevelop the same area; that project failed and the company went bankrupt in 2016. The area has been divided into 19 sub-plots, each of which is managed by its own company, but most of those companies also were set up by Melikyan, an arrangement that the local branch of the anti-corruption organization Transparency International (TI), along with several other civil society groups, called “very suspicious.”

The campaigners also called attention to the project’s chief architect, Narek Sargsyan, a minister of urban development under the old regime, and the fact that “the project concept developed by him was approved by the previous authorities when [he] had clear conflicts of interest as he occupied high-ranking positions in the government.”

At a June meeting at the Yerevan municipality, which brought together government officials and civil society representatives to discuss the project, the government’s point man for the project, Serge Varak Sisserian – the chief of staff for Deputy Prime Minister Tigran Avinyan – defended the convoluted arrangement it had inherited from the previous authorities.

“Yes, they [the 19 companies managing the individual sub-developments] were founded by one person, but we coordinated the whole process,” Sisserian said.

TI and the other civil society groups, in a statement following the meeting, said that Sisserian’s remarks “displayed an attitude to civil society similar to that of the former regime.”

TI has gathered evidence about potential corruption in the project, which they have provided to Armenia’s Special Investigative Service, who sent it on to police. The police declined to undertake a criminal prosecution but TI has appealed to the state prosecutor’s office and is still awaiting a decision.

“The company that got the construction contract is the exact same one that failed to complete the same Firdowsi reconstruction project in 2007 and 2008,” Hayk Martirosyan, a legal expert with Transparency International, told Eurasianet. “The company needs to show financial documents providing a guarantee to the government that it won’t fail this time. We asked the government to show us the documents and they have refused, saying it is a ‘trade and banking secret,’” he said.

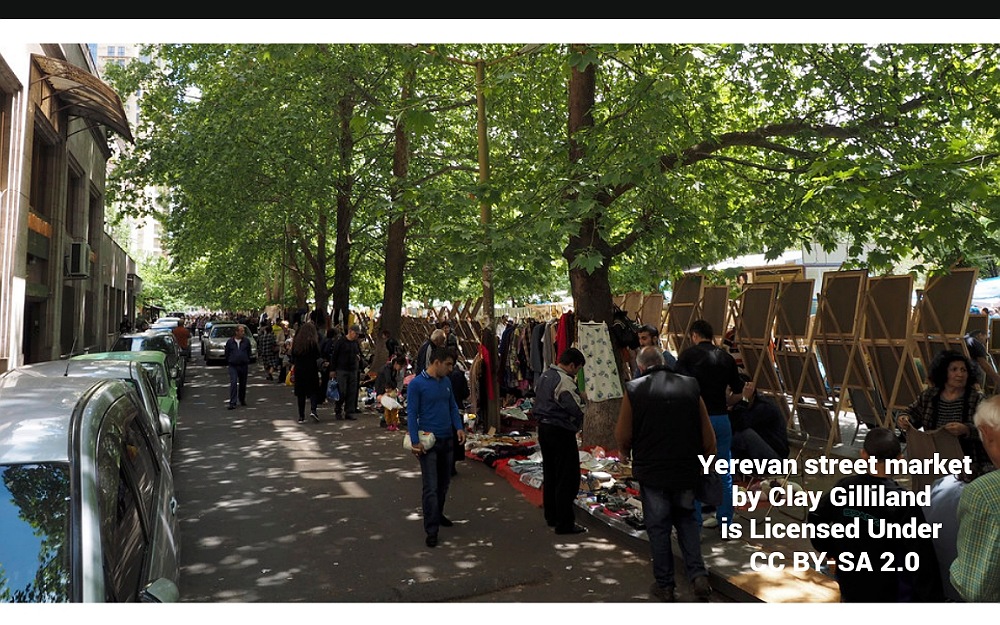

Today, Firdowsi isn’t much to look at. Immediately following the collapse of the Soviet Union and Armenia’s independence, it became a lively commercial district. But over the past three decades, a series of demolitions connected to uncompleted renovation projects has left the area nearly a wasteland. Until 2017 it held an informal clothing market but that year the authorities cleared the area and now only a handful of sad shops remain.

Residents say the crackdown on commerce in the neighborhood was intentional.

“They closed the market so people don’t have money for lawyers or any reason to live here,” said Ara Shahumyan, whose family has lived in the neighborhood since the 1920s. “They did it to weaken the community.” He showed a reporter around the neighborhood, pointing out the empty houses of several former neighbors who have moved abroad. Under the government decree regulating the development, he doesn’t even have the option to own property in the new development, he complained – his only option is to sell.

To many, the project recalls the development of Northern Avenue, completed in 2007 and now the pedestrian center of the city, lined with chain stores and restaurants. In that case, too, the city’s heritage was destroyed and the former residents were unfairly compensated for losing their homes. In some cases they were violently forced to leave. A group of those displaced sued the Armenian government in the European Court of Human Rights and won a 2.5-million euro compensation.

“It is a mirror image of Northern Avenue. The state takes the property of its rightful owners and gives it to a private entity – the only difference is that unlike Northern Avenue, they are not using violence but under the new government the developer is blackmailing people” by threatening that their homes will be demolished whether or not they agree, Sargsyan of the Yerevan Heritage Protection Committee said.

Few specifics about what the new development will entail have been released, other than a government video rendering of part of the area. Sisserian told Sputnik Armenia that the area would include museums and souvenir shops and would be a tourist attraction.

Sisserian has said that construction of the new project should begin by the end of 2020.

Meanwhile, residents are waiting. Siranuysh Aghajanyan is one of several artists who rent studios there. “This has been the best place I have worked. It’s in the center, but natural and isolated enough for an artist,” she told Eurasianet. The controversy over the neighborhood also has inspired her to explore more political themes in her art – as long as she can. “We have a lot of ideas,” she said, “but we’re afraid of doing anything major while the fate of Firdowsi is so uncertain.”

This story was originally published by Eurasianet Eurasianet © 2020

North Korean women in China catch ‘Disco Fever’

Russia’s Full-Scale Invasion Pushes Ukraine’s Drive Toward Digitization

As UN Warns Kabul’s Groundwater Could Deplete by 2030,Residents Wait for Hours to Collect Water

Despite Risks,Unaccompanied Child Migrants Keep Crossing US Border

Mary Jane Veloso, a Filipina on Death Row in Indonesia,is Coming Home

Trapped in Lebanon, African Migrants Face Unemployment and Rockets

The Impact on a Ukrainian Family During 1,000-Days of Russia’s War

Subscribe Our You Tube Channel

Fighting Fake News

Fighting Lies