The junta prioritizes cracking down on its opponents over ensuring law and order, attorney says.

By RFA Burmese

Myanmar’s military authorities are failing to arrest and charge perpetrators of violent crimes like armed robbery and murder, say crime victims and regime opponents, who accuse the junta of fighting political foes instead of crime.

Violent offenses across the country–including the largest two cities, Yangon and Mandalay–have largely gone unpunished in the wake of the junta’s recent amnesty, during which more criminals than political dissidents were freed, they said.

The regime, formally called the State Administration Council, said last week it had released 5,774 prisiners, including 712 political prisoners, to mark a national holiday.

That brought the total number of amnesty grantees to 62,865 prisoners since the military seized power from the democratically elected government in a coup on Feb. 1, 2021. The Institute for Strategy and Policy-Myanmar and other research groups noted that only 5,268 of them were political prisoners arrested for participating in anti-coup protests and movements.

Myanmar’s Ministry of Home Affairs, which was controlled by the military even before the coup, has not updated its public crime statistics since 2018.

A statement issued by the military regime in November did not specify the crimes of the inmates who were freed. A July 2021 amnesty dismissed criminal cases pending before the courts filed prior to the coup for 11 types of offenses, including theft; larceny; arrests made without a warrant; and violations of gambling, excise and forestry laws.

More recently, Monywa District People’s Defense Army, a militia group in Sagaing region’s largest city, issued a statement in September, saying that criminals freed from prison under junta amnesties included those sentenced during the previous civilian-led government for violent crimes such as rape, murders and theft, as well as members of criminal gangs who committed new crimes.

As of Monday, the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners, a Thailand-based rights group, recorded 6,316 arrests for political reasons since the coup and 3,371 releases, suggesting that others freed by the junta had been imprisoned for other crimes.

In urban centers in the country of 54 million people, women and elderly have become targets of robbers and muggers who commit crimes in gangs.

Yangon resident Myo Aye said he was robbed of the equivalent of about U.S. $72 by muggers on an Indian-made motorbike while standing at a crowded bus stop in Yangon on Nov. 1.

The following day, three men with knives robbed a hardware store in the city’s Pabedan township in downtown and stabbed the owner before they stole his car, his cell phone and some cash.

Similarly, there was a gang robbery in Mandalay, Myanmar’s second-largest city by population, on the same day. Nwe Ni, who was robbed of her motorbike and necklace in the incident, said residents must live amid the lawlessness.

“I didn’t even have time to scream,” she said. “It was in broad daylight while many people were going to the market. The robbers were a group of young men. It was very scary.”

‘State of anarchy’

On Oct. 30, award-winning author College Star, 70, and his wife, a retired schoolteacher, were stabbed to death during a robbery at their home in Yangon’s Mingalar Taung Nyunt township.

“The authorities cannot find the murderers,” said neighbor Mying Oo. “If the authorities want to restore law and order, they should try to take action to catch the perpetrators. Now, we are now living in a state of anarchy.”

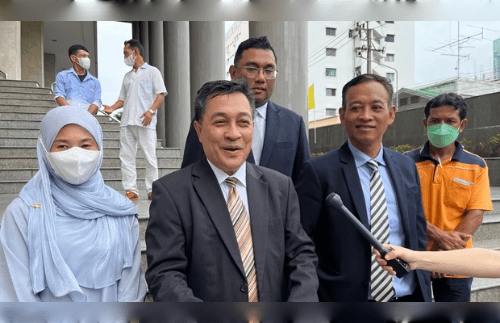

Bo Bo Oo, a former parliamentarian for Yangon’s Sanchaung township, said the junta was responsible for the increased threats to people’s lives and property.

“The protections under the law are totally gone now,” he told RFA. “There is no guarantee for individual citizens. The ruling regime is arresting and killing people at will and for no reason, so it is not surprising that the security condition has deteriorated under such a regime.”

Bo Bo Oo said that military regime leaders who seized power from Myanmar’s elected government in a February 2021 coup have shown no capacity to restore law and order.

Minh Zaw Oo, executive director of the Myanmar Institute for Peace and Security, said security conditions for civilians in Myanmar are now the worst since the military coup.

“Now, we are witnessing an increasing number of crimes like bank robberies or robbery- homicide cases,” he said. “It’s true that the security condition of civilians has gone down vastly.”

Junta leader Senior Gen. Min Aung Hlaing said during a regime meeting on Nov. 1 that a country cannot be stable without law and order, especially if people live in fear of getting mugged.

An attorney, who declined to be identified for safety reasons, said despite Min Aung Hlaing’s comments, the military has prioritized strengthening its rule over cracking down on criminals.

“The activities of the police forces, which are controlled by the military council, are now almost at a standstill,” he said. “They are doing nothing concerning crime prevention, investigations or prosecutions.”

Instead, authorities are mainly focused on cracking down on sympathizers of the parallel National Unity Government and members of People’s Defense Force, the NUG’s armed wing and have abandoned ensuring the safety of citizens.

“Under these circumstances, there are increased crimes, instability and lawlessness around the country,” he said.

Translated by Ye Kaung Myint Maung for RFA Burmese. Written in English by Roseanne Gerin. Edited by Paul Eckert.

Copyright © 1998-2020, RFA. Used with the permission of Radio Free Asia, 2025 M St. NW, Suite 300, Washington DC 20036. https://www.rfa.org.