Viewers argue about the show’s merits despite it not being officially available behind the Great Firewall.

By Lucie Lo and Wang Yun for RFA Mandarin, Yitong Wu and Chingman for RFA Cantonese

A Netflix adaptation of Chinese sci-fi author Liu Cixin’s “The Three-Body Problem” has sparked mixed reactions in China, with some complaining of a lack of nuance, that much of the action takes place outside of China and that key characters are played by non-Chinese actors.

But others praised it as a well-made adaptation for Western audiences and had made improvements in female characters.

The show, which premiered on March 21 just as a man was sentenced to death for fatally poisoning one of its producers, billionaire Lin Qi, was Netflix’s most-watched English TV show from March 25-31.

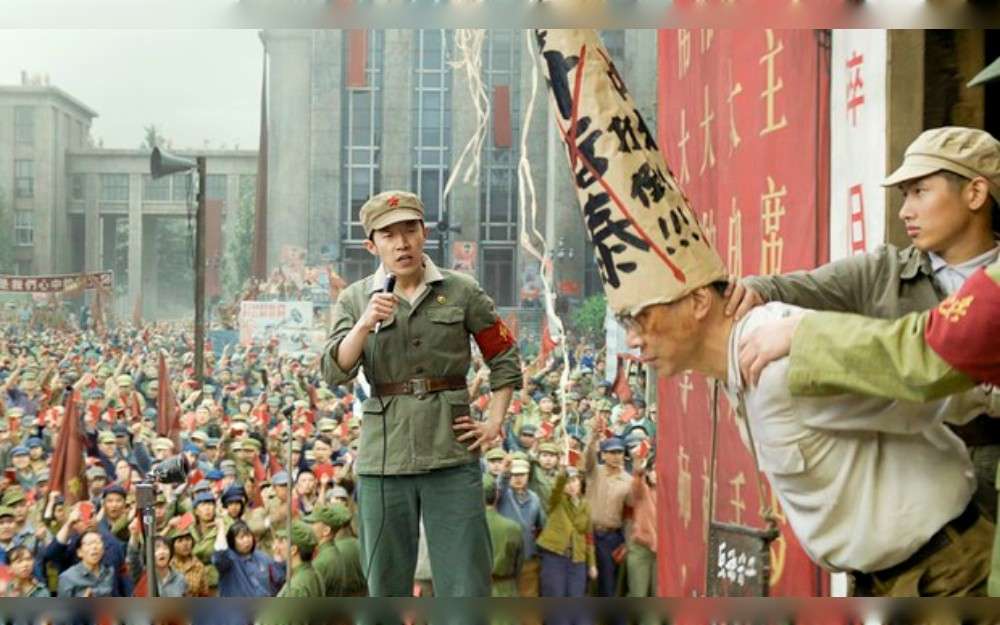

It features scenes of a political “struggle session” from the Cultural Revolution under the rule of late supreme leader Mao Zedong, in which physicist Ye Zhetai is beaten to death by Red Guards after being denounced by his own wife, for teaching the Big Bang theory and therefore failing to deny the existence of God.

The scenes — omitted from a homegrown adaptation of Liu’s books produced by Tencent — are likely one of the reasons that the show is officially blocked in China.

But viewers in China still discussed it widely after using circumvention tools to get around the “Great Firewall” of government censorship.

Violence under Mao

Reports emerged on social media in January that the show would likely be blocked on the orders of the ruling Chinese Communist Party’s Central Propaganda Department.

While RFA was unable to confirm those reports independently, the political violence of the Mao era remains a highly sensitive topic for the government today and has gotten other films and TV shows banned before.

Nonetheless, enough people were able to see the show to discuss and search for “Three Body beating/hanging scene” on the Weibo social media platform, according to trending searches spotted by RFA this week.

The hashtag #3BodyProblem# garnered billions of views on Weibo, according to The Guardian newspaper, and notched up a 6.9/10 score on Douban’s review site, compared with an 8.7 score for Tencent’s Chinese-made version of the show, which premiered in January.

Mixed reviews

Some appear to have been underwhelmed by the show, which transplants a good deal of the action to the United Kingdom, and changes the genders, ethnicities and names of several major Chinese characters in the book.

One post complained that all of the best Chinese male leads had been given to non-Chinese actors. The show’s producers have said they wanted the whole world to be depicted.

Douban user Victor’s Catzz described the Netflix version as “quite good,” adding that it improves considerably on Liu Cixin’s writing of female characters and foreigners, which he thought was “a mess anyway.”

“What’s wrong with Netflix making reasonable adaptations for English-speaking audiences?” the user wrote in a post titled “A minority opinion.”

@Rick Ro$$ from Shaanxi disagreed, commenting: “Netflix has switched up a lot of the ideas in the original work. Those ideas were precisely the essence of The Three-Body Problem.”

One comment thought pro-Beijing “little pinks” had hijacked the show’s rating on public review sites, while others argued over whether the characters were more two-dimensional in the Chinese-made TV show or in the Netflix version.

@engauge commented from Guangdong that the “melodrama” in the Netflix version had glossed over the “global vision and apocalyptic background to the political and social turmoil in the original work.”

Sichuan user @Drunken_and_dreamed_98147 wanted to know why, if the show’s setting had been transplanted elsewhere, the writers had kept the Cultural Revolution scenes.

“Why not change that era to show discrimination against black people in America?” the user wanted to know. “Wouldn’t that satisfy foreign requirements for political correctness even more?”

Cultural Revolution

Meanwhile, an article on the Chinese film review website Mtszimu praised the adaptation as “not only a new interpretation of Liu Cixin’s original work but also an important contribution to global science-fiction literature.”

The People’s Liberation Army website China Military Online took issue with the show keeping some characters as Chinese, while not portraying a modern China, only the Maoist past. Even though some TV shows and movies are blocked, government-related sites will comment on them.

Alexander Woo, executive producer of Netflix’s version of “The Three-Body Problem,” told The New York Times in a recent interview that scenes of the 1966-76 Cultural Revolution held a special meaning for him as his family lived through that era, as did the family of the episode’s director Derek Tsang.

“We give a lot of credit to him for bringing that to life,” Woo told the paper. “He took enormous pains to have every detail of it depicted as real as it could be. I showed it to my mother, and you could see a chill coming over her, and she said, ‘That’s real. This is what really happened.'”

Tsang told RFA’s Cantonese service in an interview in January that he felt the depiction of the Cultural Revolution was a key part of the show.

“It is becoming increasingly difficult to depict that period in any way [in China],” he said. “But it is a very important part of history.”

“If we are honest, we can all learn from it if we face up to it and take it seriously. It’s important to show everyone how ridiculous that period was,” Tsang said.

U.K.-based writer Ma Jian said one of the reasons that the Cultural Revolution is still so sensitive in today’s China is that President Xi Jinping is drawing on Mao Zedong’s playbook even now, prompting fears that he is going to drag the country back to that era.

“Xi Jinping wants a return to the Cultural Revolution, and to imitate Mao Zedong,” Ma said. “[But] the whole world has seen through the horror of totalitarianism.”

Translated with additional reporting by Luisetta Mudie. Edited by Malcolm Foster.

“Copyright © 1998-2023, RFA.

Used with the permission of Radio Free Asia,

2025 M St. NW, Suite 300, Washington, D.C. 20036.

https://www.rfa.org.”