Joyce Huang

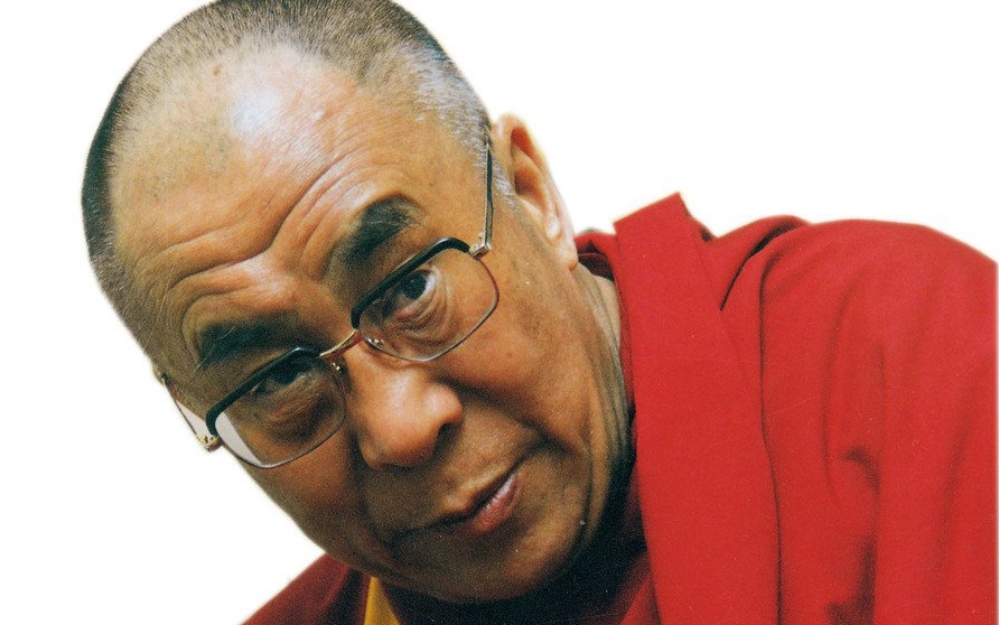

Beijing has reacted strongly to recent remarks from Tibet’s exiled spiritual leader, the Dalai Lama, who in late March suggested that his successor may come from India.

Chinese authorities have insisted that the selection of the next Tibetan Buddhist leader must comply with Chinese laws” – an indication that China looks set to repeat another reincarnation controversy similar to that of the 11th Panchen Lama’s anointment in 1995.

The legitimate holder of that title, Gedhun Choekyi, who the international society suspects was forced into disappearance by China, turns 30 this Thursday.

Two Dalai Lamas?

Analysts say the possibility of two Dalai Lamas – one chosen by China and the other in exile – is real.

China feels that it can use the next pro-Beijing Buddhist leader as a propaganda tool to strengthen its narrative that it is protecting Tibetan culture and Tibetan language.

But such repressive policies can only backfire, said Tom Grunfeld, a professor at Empire State College of the State University of New York.

“By repressing them, they create disloyalty to the state. The consequences of their [China’s] action is the exact opposite of what their goals are. And the more repression, the more disloyalty,” said Professor Grunfeld.

“And so, in Tibet, on the surface, things are calm, but under the surface, there’s enormous anger against the Chinese,” added the professor.

Golden Urn

China may resort to drawing lots from a golden urn to select the successor of the 14th Dalai Lama as it had done so in choosing the 11th Panchen Lama.

The use of a golden urn was introduced by the Qing Dynasty in the late eighteenth century to signify its authority over Tibetan leaders.

But the method won’t win the hearts and minds of Tibetan Buddhists, neither will they venerate any local religious leaders chosen through the urn, said Dawa Tsering, Taipei-based representative of H. H. the Dalai Lama.

“The drawing of lots from a golden urn means nothing but a bottle, which has no religious and cultural value to Tibet. Not a single Tibetan has had faith in the so-called Han Panchen Lama, recognized by China,” Tsering said.

Neither will Tibetans venerate the successor of the Dalai Lama if he’s named by Chinese authorities, he added.

Professor Grunfeld agreed, saying that the fact that many Tibetans refuse to hang the picture of the Panchen Lama, recognized by China, is a “political statement” that they don’t accept the incumbent Panchen Lama.

Power Play

Tsering criticized that China’s power play in Tibet has had a devastating effect on the Tibetans’ practice of Buddhism and cultural heritage.

He added that China, under the leadership of Chen Quanguo, who now serves as the Communist Party’s secretary in Xinjiang, has long implemented measures to transform Tibetans, similar to the practice in Xinjiang’s re-education camps.

Authorities in Tibet can’t be reached for comment and VOA’s calls to the Tibetan Commission of Ethnic and Religious Affairs got hung up on.

The Dalai Lama fled to India in 1959 after a failed uprising against Chinese rule and has since worked to promote religious and cultural autonomy for his people.

China has called the exiled leader a dangerous separatist – an accusation the Dalai Lama has long flatly denied.

He told a group of visitors in March that he has ceased to appeal to the United Nations since 1974 to declare Tibet’s independence.

Instead, he hopes to engage with Chinese officials through dialogues, seek to pursue true autonomy for all 6 million Tibetans, wrote Chinese dissident Yang Jianli in an article, who led a delegation to visit and meet with the Dalai Lama in March.

No Official Meetings

But no official meetings have been made between his exiled government and the Chinese authorities after 2010.

According to Grunfeld, China held a tight grip on the monasteries and repression in society is also tight. Thus, any resistance to the Chinese rule is doubtful to succeed.

At least 154 Tibetans are confirmed to have resorted to self-immolation as a way of protest against China.

In spite of such protests, China shows no sign of easing its controls in Tibet.

“Self-immolation represents a form of individual [protest], which may hurt China’s [international] image, but won’t rock the boat to change the political landscape [in Tibet],” said Kou Chien-wen, a professor of East Asia Studies from National Chengchi University in Taipei.

Kou said Tibet won’t be left alone now that China is tightening controls all over the country.

Neither will China give up its authority to designate a pro-Beijing leader in Tibet — similar power it has in Hong Kong, where China has the final say in the territory’s chief executive, Kou added.