Mutually exclusive interpretations of the words “peace” and “compromise” block any capacity to imagine a future together.

Marina Nagai and Sophia Pugsley /Eurasianet

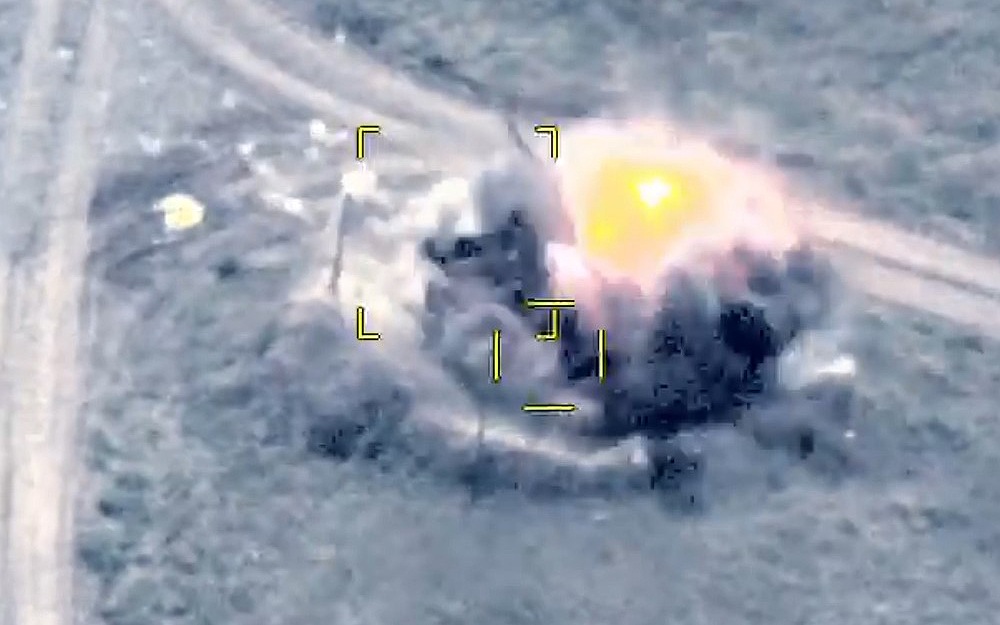

There is a common acknowledgement that the war is about identities, sacred values, and conflicting histories, but there has been staggeringly little understanding of how big a role public attitudes and sentiment play in political decision-making. Indeed, decisions in Baku and Yerevan are more often explained using hard security and geopolitical terms. An example of this, which came as a surprise for many, was the mass discontent and spontaneous mobilization in Baku following clashes with Armenia in July, when thousands of people took to the streets to call for an armed resolution to the conflict and signed up to volunteer on the front line.

At the end of 2018, the peacebuilding NGO International Alert conducted a qualitative study of public attitudes in Armenia, Azerbaijan and Karabakh. This study was, in many ways, eye-opening and deeply worrying as, despite its purpose to envision peace, it found overwhelming acceptance of violence and human sacrifice as the only way to solve this conflict; many felt war was inevitable.

For example, when respondents stated a preference for “peace,” definitions differed radically, underscoring why it has proven so elusive: an absence of violence, a ceasefire, and stability for Armenians; restoration of what they see as historical justice through the return of IDPs and lands, dignity and international order for Azerbaijanis. These mutually exclusive interpretations of the word “peace” keep the sides in parallel universes and block any capacity to imagine a peace together.

Political leaders benefit from an ambiguous, rhetorical use of “peace,” mostly for external audiences. Over decades of working on and in the Nagorny-Karabakh context, we have seen the ebbs and flows of the mediation process with phases of “creating more favorable conditions for preparing public opinion for peace” in 2007, “facilitating people-to-people contact for peace” in 2014 and, most recently, “preparing the populations for peace” in 2019.

Similarly, compromise – a contentious, even taboo notion which arouses strong reactions on all sides of the conflict – is understood differently. Each side accepts compromise, but only from the opposite party; there is little reflection on what’s concessions societies and individuals are prepared to make themselves. The essential reciprocity, in which both parties give up something that they want in order to get something else they want more, is perceived as loss and an outright humiliation. Of course, some things cannot be compromised on because they cut to the core of an individual’s or group’s identity or survival. That said, unrealistic expectations delegitimize the opponent’s fears, hopes and aspirations, removing the other side from the equation altogether.

In recent days, while we are all grasping at any sign of hope for the region, it is remarkable to see that there have been desperate calls for peace from Armenians and Azerbaijanis around the world. But beyond the undisputedly symbolic and signaling value of such calls lies a challenge for peacebuilding work, as “peace” is neither ceasefire, appeasement, nor absence of war.

Peace is when people manage disagreements without violence and engage in inclusive social change processes that improve the quality of life for everyone. This is the idea of interdependent, “positive” peace that drives painstaking efforts to transform this conflict. However dry and academic they may appear, these concepts and definitions are important in the meanings they carry. Unpacking these meanings is the basis for what societies do to achieve peace, depending on how they – ordinary citizens, not political and intellectual elites – imagine and conceptualize it.

It is for a good reason that monitoring and influencing public opinion has been a key part of peace processes in other contexts, such as Northern Ireland. One place to start in the Karabakh conflict is to listen, understand, and engage with what ordinary people feel and think. This engagement means supporting them in their own search for peace; this search will likely be the hardest thing they will have ever faced, requiring considerable courage, long-term commitment, and tenacity to overcome difficulties and failures along the way.

Marina Nagai and Sophia Pugsley work on peace-building initiatives in the South Caucasus with International Alert.

This story was originally published by Eurasianet Eurasianet © 2020

Escaping from Scam Center on Cambodia’s Bokor Mountain

UN Security Council Meets to Discuss Children and Armed Conflict

10 Shocking Revelations from Bangladesh Commission’s Report About Ex-PM Hasina-Linked Forced Disappearances

Migration Dynamics Shifting Due to New US Administration New Regional Laws

UN Security Council Meets to Discuss the Maintenance of International Peace and Security and Artificial Intelligence

Winter Brings New Challenges for Residents living in Ukraine’s Donetsk Region

Permanent Representative of Israel Briefs Press at UN Headquarters

Hospitals Overwhelmed in Vanuatu as Death and Damage Toll Mounts from Quake

Subscribe Our You Tube Channel

Fighting Fake News

Fighting Lies