The Southeast Asian country saw a 35% rise in 2022 from 2021 in girls 10-14 years old giving birth.

Camille Elemia/Manila

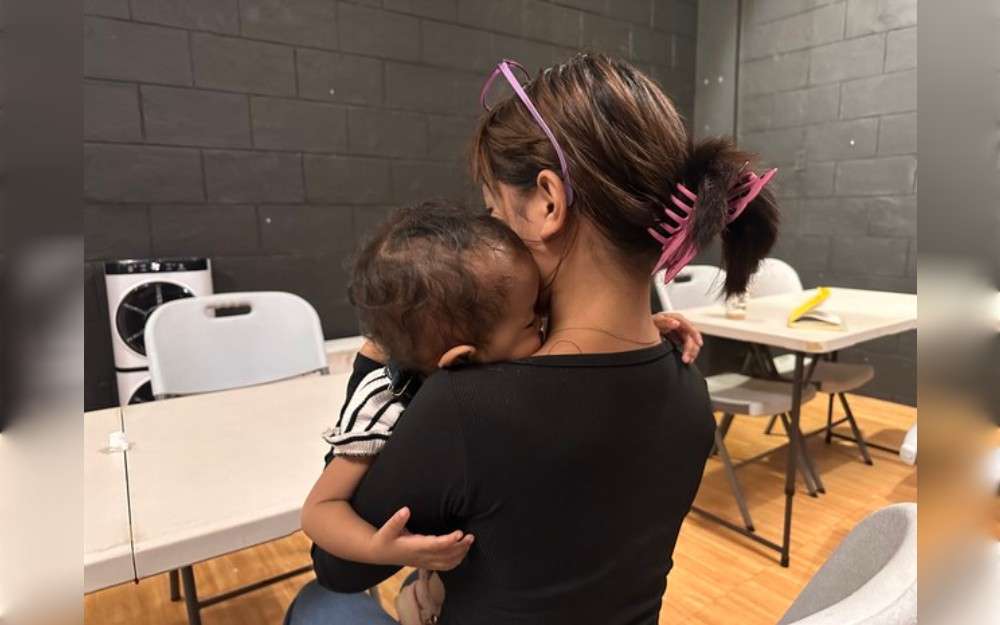

“Mae” (not her real name), a Filipina from a village north of Manila, has a 2-year-old daughter whom she gave birth to when she was 13 years old.

Having received no sex education at school – she was in the sixth grade two years ago – or from her family, she said she did not know about the consequences of having unprotected sex.

For “Mae,” those consequences include quitting school to take care of her infant. Now 15, she said she did not know if and when she could continue her education.

“Mae” requested that BenarNews identify her only by a pseudonym because she wanted to retain her privacy.

Around 500 adolescents give birth every day in the Philippines, which prompted the government in 2019 to declare adolescent pregnancies “a national social emergency.”

The situation is still and will remain a social emergency “unless significant and targeted interventions are put in place,” according to Vivien Martin, director of sponsorships for Save the Children Philippines.

“The data shows a worrying trend [of teenage pregnancies] that has not been adequately addressed by current policies and programs,” Martin told BenarNews.

The high numbers of teenagers becoming mothers is mainly because they lack access to reproductive health services amid conservative opposition and poor regulations, Philippine child rights activists and health experts said.

They added that it was urgently necessary for the Philippine Senate to pass a bill it recently discussed that would increase teenagers’ access to contraception, expand sex education, and devise effective programs that reach communities that need them the most, among other remedies.

Lolito Tacordon, deputy director of a Philippine government agency, the Commission on Population and Development, called the situation “alarming” and explained why high numbers of adolescent births constitute a social emergency for the country.

“Adolescent pregnancy is a social issue that has long-term irreversible individual and societal impacts,” Tacordon told BenarNews.

Those who give birth so young are then caught in “a vicious cycle of intergenerational poverty,” she said.

Tacordon described the ripple effect.

Childbearing in adolescence carries increased risks for poor health outcomes for both mother and child, Tacordon said.

Additionally, because many of the young mothers may need to leave school to look after their infant, it also leads to lower educational attainment and employability for the group for generations.

This, in turn, can negatively affect the quality of the country’s labor force and its economic development.

Teenage mothers – and the country – lose lifetime earnings of around 33 billion pesos (U.S. $578 million) from missed opportunities, according to a 2016 study commissioned by the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA).

The study assumed the teenage mothers would start earning income at 20, and it defined lost income as the difference between what they would earn without finishing high school compared to what they could have earned – a higher wage – with a high school diploma.

Teenager “Mae’s” neighbor, 18-year-old “Anna,” (not her real name), who is also a mother, seems to have instinctively understood the importance of finishing high school.

“Anna” became a mother at 15, three years ago. The father of the baby wanted her to terminate the pregnancy, but she refused.

After a brief break to take care of her daughter, the now 18-year-old returned to continue her education and aims to complete high school in two years.

“My dream is to finish college so I can help my mother and secure my child’s future,” “Anna” said. She also asked BenarNews not to use her real name, citing concerns for her privacy.

“I tell my siblings and cousins not to follow what I did because being a teenage mom is very difficult. You cannot get your life back.”

“Mae” and “Anna” live in a village called Payatas, which is located in Quezon City, Metro Manila. They said they don’t feel like the odd ones out because there are many young mothers in their community.

These high numbers give the Philippines the dubious distinction of having the highest adolescent birth rate among fellow member-states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, according to the U.N. Population Fund (UNFPA).

Although 2022 figures – the latest official data available – show a decline from 2017 in 15-19-year-olds giving birth, they also reflect a disturbing increase in pregnancies in another age group – 10- to 14-year-old girls.

In the younger group, girls becoming mothers rose 35% in 2022 to a little over 3,000 from just a year previously, when it was 2,320. The absolute number isn’t very high, but if it reflects a trend – considering the data for slightly older girls – it should worry child rights advocates.

In 2022, the number of 15- to 19-year-old girls giving birth fell to 5.4% from 8.6% in 2017, but the problem is still a “national social emergency,” experts and advocates said, because the absolute numbers are so high.

Health experts and advocates have blamed inadequate access to reproductive health education and services such as providing contraceptives to teenagers. Philippine law says those who are 18 and under need parental consent to access contraceptives.

The rule applies even to mothers who are 18 and under.

The restriction adds to the already high risks of health complications – severe neonatal problems and even – for the young mothers and their babies – according to a 2016 UNFPA study.

Additionally, girls under 15 are twice as likely to die from complications during pregnancy or childbirth, than women between the ages of 20 and 30.

Government data revealed a related concern – a serious one.

Of those adolescent girls who registered their babies’ births, a majority became pregnant from sexual relations with older men – in some cases older by at least 10 years. This trend, experts said, presents the underlying issue of abuse of minors, as the age of consent is 16.

A complex issue

Cultural barriers are also factors that contribute to teenage pregnancies.

For instance, child marriage is still practiced in some communities, which consider it part of tradition and culture.

Child marriage was declared illegal only in 2022, and it is difficult to monitor the practice, child advocates said. Local authorities tend to not be informed about the laws, thus exacerbating the problem, they said.

Just as the government criminalized child marriage only recently, it also raised the minimum age of consent sexual consent from 12 to 16 only two years ago. It was a welcome change, but too late, advocates said.

Vivien Martin, of Save the Children Philippines, said that another cultural issue is when schools have to deal with teachers whose personal beliefs prevent them from instructing on sex education – called “comprehensive sexuality education” in the Southeast Asian nation.

“Comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) gives young people accurate, age-appropriate information about sexuality and their sexual and reproductive health, which is critical for their health and survival,” according to the World Health Organization.

CSE covers the same topics as sex education but also covers broader issues such as relationships, attitudes towards sexuality, gender relations, among others, according to some experts.

It was a compulsory course for all public schools under a directive of the Education Department for all public schools, but the lack of a law means private schools don’t have to follow the directive.

That’s the reason advocates are calling for the passage of the Adolescent Pregnancy Prevention Bill, which was approved in the House of Representatives in September 2023 and is currently being debated in the Senate, where it needs to pass a second and third reading.

The draft bill’s provisions seek to strengthen and expand the comprehensive sexuality education program, ensure access to sexual and reproductive health services for adolescents with the necessary guidance from health workers, and provide social protection for at-risk and teenage mothers, among other provisions.

Now, the section of people that need to be convinced to heed the potential law is the one that believes the bill will end up teaching children how to have sex or encourage them to have sex.

Copyright ©2015-2024, BenarNews. Used with the permission of BenarNews.