While there were still serious hopes for press freedom in Asia and Oceania in 2010, the past decade has been marked by general glaciation. Counter-models to totalitarian practices, development of a populism which profites hatred of journalists, concentration of the media to the extreme … The challenges that await this region of the world are absolutely considerable.

One of the lessons from the 2020 Ranking in Asia and Oceania is that press freedom is potentially at risk regardless of the country. The proof with Australia (26th), formerly cited as a regional model, which lost five places at once, notably due to a double search of the federal police, at the home of a journalist and at the headquarters of the public audiovisual. This precedent now poses very serious threats against the secrecy of sources and investigative journalism. The event was, moreover, an opportunity for Australians to realize that they have absolutely no constitutional guarantee concerning the freedom to inform and to be informed.

It is all the more alarming that it is in Asia that we find the worst country in the world in this area: after a semblance of openness of the regime to foreign journalists on the sidelines of the summits of June 2018 and February 2019, which brought together President Trump and “supreme leader” Kim Jong-un, North Korea (180th, -1) regained the last place in the ranking in 2020.

In the race for repression, it is still closely followed by China (177th), which continues to perfect its model of hyper-control of information and repression of dissenting voices, as evidenced by the arrest, in February, two Chinese citizens who decided to cover the coronavirus crisis. Above all, China is the largest prison in the world for journalists, with nearly a hundred of them, including a large majority of Uyghurs, who languish behind bars.

Counter-models, a geopolitical challenge

If Vietnam (175th) wins a place in the 2020 ranking, it is simply because the repression was such in 2018 that the country benefits from a mechanical effect this year. Laos, for its part, still loses a place (172nd), in particular because of the repression of the regime against the emergence of a shy blogosphere.

Another novelty of 2020: these four countries, ruled by single communist parties, are joined in the “black zone” of the RSF Ranking by a fifth regime which has passed the lead in terms of absolute information control: Singapore. With its Orwellian law supposed to combat “false information”, the city-state loses seven places from one year to the next (158th).

The Sultanate of Brunei (152nd) has tightened its arsenal of information control by incorporating into its penal code the death penalty for any statement or writing deemed blasphemous towards the Muslim religion. Two other regimes in the region have managed to perfect their system for suppressing dissenting voices a little more: Prime Minister Hun Sen’s Cambodia (144th, – 1) and General Prayut’s Thailand (140th, – 4).

Pakistan (145th), which has brought down almost all the traditional media, is now increasing the number of attempts to silence critical voices online; result, the country retrograde by three places. Similarly, in trying to impose liberticidal laws, Nepal lost six places (112th).

Political and religious intolerance

The geopolitical challenge represented by these counter-models of press freedom is accompanied by the assertion of a national-populism which does not tolerate critical journalism and assimilates it to anti-government behavior and, by extension, anti-national.

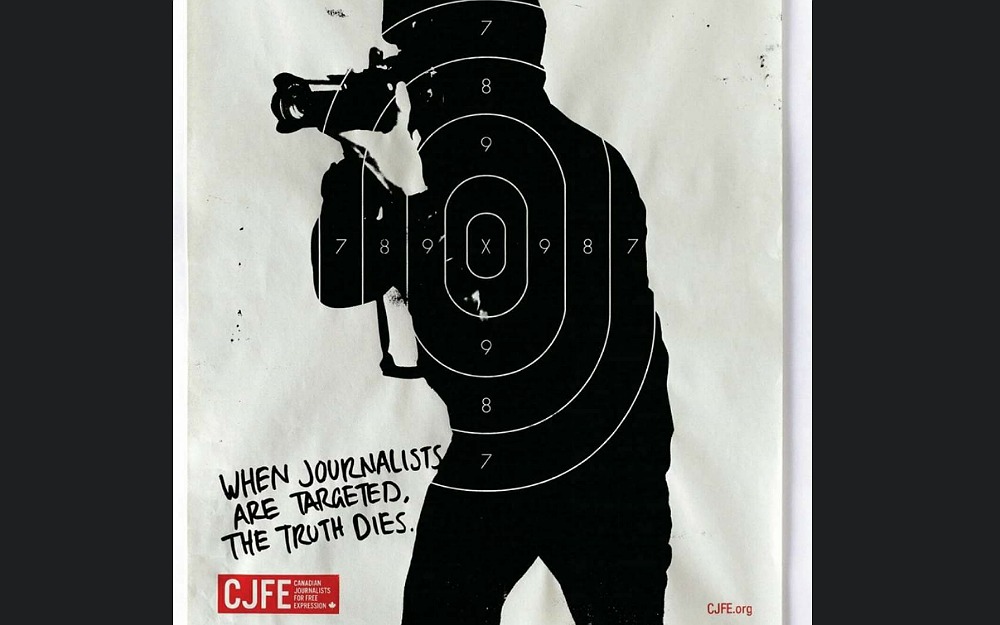

This state of affairs places reporters who try to do their work on the front line. They are the subject of police violence, as we have seen in Sri Lanka (127th, – 1) and during the pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong (80th) – the semi-autonomous territory lost seven places, one of the most sharp declines in Asia.

They are also attacked by pro-government political activists, as was the case in Bangladesh (151st, – 1), the Philippines (136th, – 2) and India (142nd, – 2). By cutting off communication to the eight million people in the Kashmir Valley, New Delhi has also imposed the biggest electronic curfew in history.

The Indian example is also characteristic of a considerable intolerance of religious extremist circles towards journalists who do not follow the official line, as is the case of the Hindu nationalist right, but also of the Taliban in Afghanistan ( 122nd, – 1) or certain Buddhist fundamentalists in Burma (139th, – 1) – all always quick to impose their vision of the world on the media.

Troll armies

This ideological hatred against the very idea of an independent press finds a natural relay on the Internet, a privileged battleground of the information war. Physical attacks on reporters are often accompanied, or even preceded, by threats made online by armies of trolls and click farms. In Asia, these little digital soldiers represent the spearheads of this uninhibited national-populism, which is largely fueled by disinformation and calls for hate online.

In this very complicated context, the press plays an absolutely decisive role in the success of the democratic exercise. This is the case in Indonesia (119th, + 5), where President Jokowi has all the cards in hand to place press freedom at the heart of his second mandate.

The performances of Malaysia (101st, + 22) and the Maldives (79th, + 19) confirm the absolutely decisive role of a political alternation to allow an improvement of the working environment of journalists and to fight against the phenomenon of self-censorship.

The press also manages to establish itself as a major player in emerging democracies such as Bhutan (67th, + 13), East Timor (78th, + 6) or Samoa (21st, + 1). In countries where the government is less tolerant of critical media, such as Fiji (52nd) or Mongolia (73rd, – 3), journalists also manage to resist, notably thanks to legal guarantees.

Concentration and polarization

In established democracies, governments are happy to use national security as an excuse to question the free exercise of journalism. It is regularly observed in South Korea (42nd, – 1), where the law threatens extremely severe penalties the publication of information deemed sensitive, in particular on North Korea.

One of the major threats to press freedom in the democracies of Asia and Oceania remains the consequences of an ever-increasing concentration of the media. This is the case in Japan (66th, +1), where the newsrooms remain very dependent on the management of the “keiretsu”, immense conglomerates favoring economic interests.

These commercial logics hamper the independence of the media all the more because they tend to favor excessive polarization and a search for sensationalism, as is the case in the Tonga Islands (50th, – 5), in Papua New Guinea (46th, – 8) or Taiwan (43rd, – 1). Even the regional model, New Zealand (9th), lost two places in 2020 due to the persistence of an ultra-concentrated media landscape. The proof that, wherever in the world you want to exercise this right, press freedom remains an endless struggle.

Copyright ©2016, Reporters Without Borders. Used with the permission of Reporters Without Borders(RSF), CS 90247 75083 Paris Cedex 02 https://rsf.org

Escaping from Scam Center on Cambodia’s Bokor Mountain

UN Security Council Meets to Discuss Children and Armed Conflict

10 Shocking Revelations from Bangladesh Commission’s Report About Ex-PM Hasina-Linked Forced Disappearances

Migration Dynamics Shifting Due to New US Administration New Regional Laws

UN Security Council Meets to Discuss the Maintenance of International Peace and Security and Artificial Intelligence

Winter Brings New Challenges for Residents living in Ukraine’s Donetsk Region

Permanent Representative of Israel Briefs Press at UN Headquarters

Hospitals Overwhelmed in Vanuatu as Death and Damage Toll Mounts from Quake

Subscribe Our You Tube Channel

Fighting Fake News

Fighting Lies