Jack Adamović Davies for RFA

The monkey farm co-owned by Hun Sengny, sister of Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen, is ringed by moat-like canals, two-meter-high earthworks and a brick wall topped with razor wire.

Guards with Kalashnikov assault rifles patrol the grounds inside the farm in rural Kampong Speu province, a former employee told Radio Free Asia, a news service affiliated with BenarNews.

So, what’s there to secure behind the walls?

The answer is the captive animals within: long-tailed macaques, a breed of primate favored for medical research.

Testing on the animals helped lead to a vaccine for yellow fever. More recently, they’ve been used to test treatments for issues ranging from reproduction to obesity and addiction.

Demand for their species soared with the onset of the pandemic, as macaques were also critical in the development of the mRNA vaccines for COVID-19.

Once an unremarkable player in the business of providing the animals for a global research industry, Cambodia has become a hub for exports of long-tails – a lucrative but shadowy business tied to the nation’s political elite.

In 2022, Cambodian primate farms like the one owned by Hun Sengny exported macaques valued at about U.S. $250 million, according to United Nations data.

But as the business booms, questions are emerging about the origin of the monkeys that Cambodia ships around the world.

Allegations of illicit trade are at the core of a high-profile legal case brought by U.S. prosecutors against government officials.

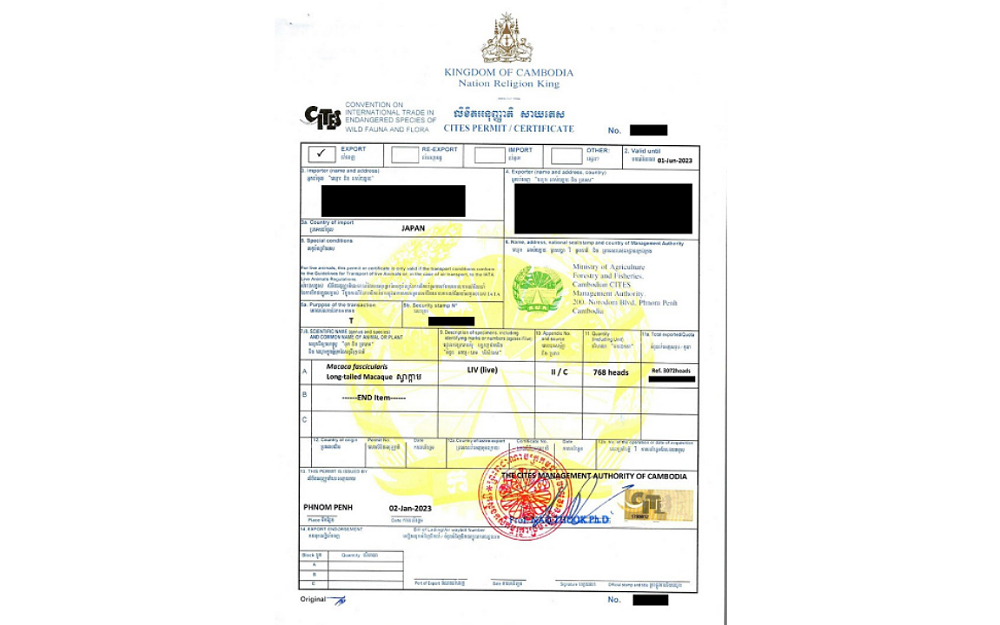

Two senior wildlife officials have been charged with issuing fraudulent export permits certifying poached monkeys as captive-bred animals to circumvent U.S. import restrictions and international treaties governing the trade in endangered species.

Cambodia’s wildlife and diversity director, Kry Masphal, was arrested in New York in November while traveling to a conservation conference in Panama. He is under house arrest near Washington, and set to face a court proceeding in Miami in June.

The second official – Keo Omaliss, who as director of Cambodia’s Forestry Administration was Kry’s immediate superior – remains at large.

“It’s kind of like the realization of our worst fears,” said Ed Newcomer, a recently retired U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service agent who spent 20 years investigating wildlife crimes around the world.

“When government officials, and relatives of high-powered officials, are involved in the wildlife trade, how are the Cambodian regulatory and enforcement agencies supposed to effectively enforce the law?”

The Cambodian government denies that there is a problem with illicit monkey trading in the country, despite calls by conservationists for tighter regulation of its farms for more than a decade.

The monkey business

Until recently, China was the world’s top macaque supplier. But in a bid to protect its own vaccine development efforts, Beijing banned their export, leaving Cambodia as the number-one source for a global research industry that was suddenly facing a severe shortfall.

In 2019, Cambodia exported the most primates it had ever shipped in a single year, sending 14,931 overseas for $33 million – an average cost of just over $2,271 per monkey, according to U.N. trade data.

The number of exports and the average cost per monkey has since continued to climb.

But experts say it would be impossible for all of them to have been legitimately raised and sourced according to rules that govern the use of research primates.

A study published earlier this month in One Health, a peer-reviewed veterinary science journal, found that Cambodian breeders would have needed to more than quadruple production rates to have legitimately exported the number of macaques shipped during the pandemic.

Yet, “Cambodia has historically been incapable of producing second generation offspring macaques, therefore increasing their production capacity legally seems unlikely,” the researchers wrote.

‘Too much money’

The fortified monkey farm owned by Prime Minister Hun Sen’s sister is not a part of the U.S. government’s case.

But it is a prime example of an “incestuous relationship,” as Newcomer describes it, between Cambodia’s political elite and its booming monkey business – and why it means the country’s industry is unlikely to reform.

Hun Sengny does not hold any government office in Cambodia.

But she is among the many with ties to political power – official or otherwise – who have enjoyed the fruits of being given free rein to undertake business ventures with little government oversight.

Hun Sengny did not respond to a request from RFA for comment.

Another Hun Sen ally, Agriculture Ministry Secretary of State Sen Sovann, leases land to a monkey farm under investigation by the U.S. government. And last year, a former minister signed an agreement to explore business ventures with yet another firm listed as an unindicted co-conspirator in the Kry case.

Given the stakes for the politically powerful, experts fear there is little incentive to reform Cambodia’s monkey trade, no matter the results of the U.S. trial.

“There’s just too much money in this business now for these macaques to stand a chance,” said Lisa Jones-Engel, a primatologist who now advises the animal rights group PETA.

Copyright © 1998-2020, RFA. Used with the permission of Radio Free Asia, 2025 M St. NW, Suite 300, Washington DC 20036. https://www.rfa.org.