Faiza Elmasry

Some 6,000 languages are spoken in the world, and nearly half of them are endangered, according to the UNESCO Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger.

One of them is Theron Musuweu Kolokwe’s native tongue, Subiya, a Bantu language spoken by more than 30,000 people along the Zambezi River in Namibia, Zambia and Botswana. “I think in my language,” he said. “I dream in my language. It’s the language that I was born into. I didn’t have the choice to speak it.”

That’s because, like other educated young people in Windhoek, the 33-year-old speaks a number of other languages on a daily basis, especially English and Afrikaans.

Two years ago, Kolokwe started documenting Subiya. The idea came to him while he was watching YouTube.

“Randomly, a video of someone speaking their native tongue popped up,” he recalled. “Then, when I opened it, it caught my curiosity. Then, I was like, I want to also hear my tongue and languages from my country and southern Africa in particular.”

Kolokwe is one of dozens of volunteers working with Wikitongues, a nonprofit in New York City that helps people from around the world preserve native languages that have been disappearing. Colorful vs. gray

When a language becomes extinct, says Wikitongues co-founder Daniel Bogre Udell, a culture disappears and a community loses its identity. That’s happening more often than many can imagine.

Udell, however, says language loss is not a natural culmination of progress.

“That’s really not an accident of history,” he explained. “It’s because, over the 1800s and 1900s, roughly every country in the world relentlessly worked to forcefully assimilate minorities’ cultures. I think no one would suggest that we need to be religiously or culturally or ethnically homogeneous. So, why would we be linguistically homogeneous? It’s a question about what kind of a world we want to live in: a colorful one or a gray one?”

The volunteer-based group began in 2016 as an open internet archive of every language in the world. Nearly 1,000 volunteers have submitted videos in more than 400 languages and dialects on Wikitongues’ YouTube channel. Some, like English, Farsi and Mandarin, are spoken by hundreds of millions of people. Others are unfamiliar, like Bora, spoken by a few thousand people in the Amazonian regions of Peru and Colombia, and Iraqw, spoken in Tanzania.

Inspiration and hope

The vision behind Wikitongues is simple and clear. It’s all about providing the tools and support people need to save their languages.

“Language revitalization at the end of the day is something that has to be done by the community, from the ground up,” Udell said. “There is no way an outsider organization can save someone’s language for them. We’ve had over 1,500 contributors and videos from 70 different countries. We have people from India who record dozens of languages, which is beyond their own. We have another volunteer from Scotland who is one of the last speakers of a variety of Scottish dialects. He’s in the process of reclaiming them, revitalizing, (and) building a dictionary for them.”

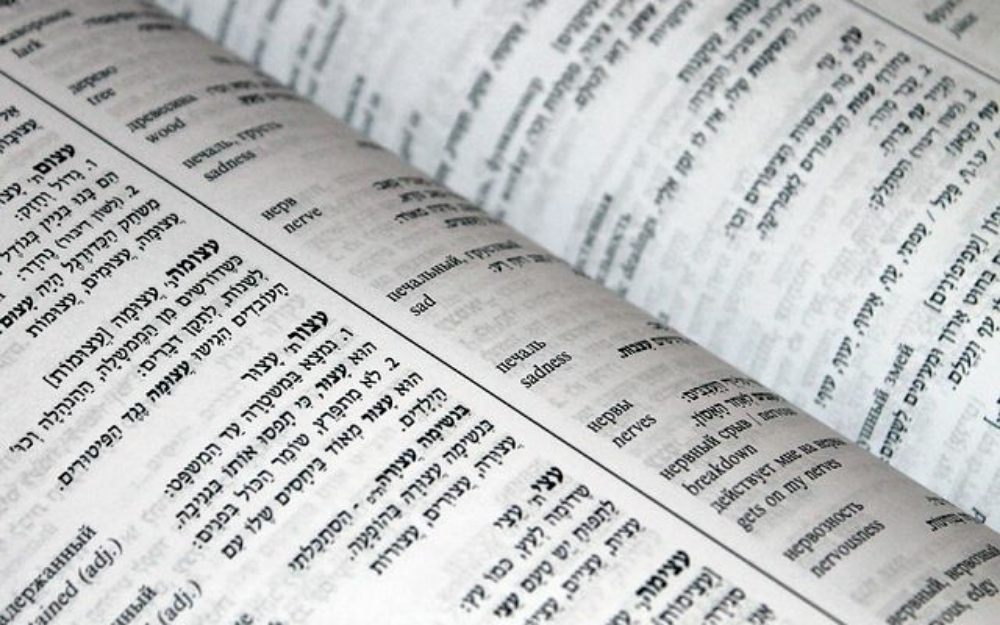

Wikitongues is also where volunteers from around the world can be inspired by the proof that reviving disappearing indigenous languages is possible. Hebrew is a good example.

Pixabay License

“Hebrew went extinct in the 4th century BC, and was revived in the 1800s and now once again it’s the mother tongue of half of the world’s Jewish population,” Udell said. “One of our tribe partners here in the U.S., the Tunica-Biloxi tribe in Louisiana, has over the past couple of years built a really lively language revival on their community. Their language went extinct in the 1940s. We’ve had contributors from the Cornish community whose language went extinct in the 1700s and was brought back in the 1900s. Their movement really got geared up when the internet arrived and new generations of Cornish speakers find each other online and use the language on a daily basis.”

Such revival success stories give volunteers like Theron Musuweu Kolokwe hope that his efforts can save Subiya and other African languages from extinction. Kolokwe’s goal is to create a dictionary, and a curriculum so it can be taught in school.

“I want the world to know about my language,” he sais. “I want to promote it, so that generations to come can speak it fluently because there is a huge influx of Western languages around here, especially in Namibia. We all learn [English] in school. It’s the business language, the language of government, and people are neglecting their native languages. So, I want to promote it so more and more people can speak it. And children can be proud of where they come from.”

With awareness and technology, Wikitongues puts people in a better position to save and revive their native languages, making the world more colorful and culturally diverse.