On Thursday, Zimbabwe marked the anniversary of its 1980 independence from Britain. The anniversary coincides with efforts to heal the wounds brought on by state-sanctioned massacres in the 1980s in which thousands of people died. In one of the most affected areas, Tsholotsho, people are opening up about reburial efforts and what they are seeking from the government.

The rural Tsholotsho area, about 600 kilometers southwest of Harare, is one the places most affected by the state-sanctioned massacres. Human rights organizations say about 20,000 people were killed in the massacres during the presidency of Robert Mugabe.

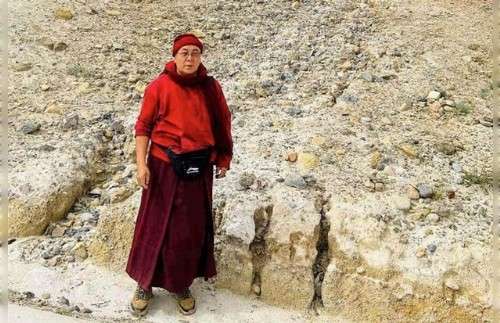

Melwa Ngwenya stands in front of one of the shallow graves of victims of Zimbabwe’s post-independence massacres in Tsholotsho district, about 600 km southwest of Harare, Zimbabwe, April 18, 2019, where he son was buried by soldiers in February 1980.

Local resident Melwa Ngwenya says a recent decision by the government of current President Emmerson Mnangagwa to allow victims in shallow or mass graves to be reburied is not something to celebrate on this Independence Day. Ngwenya says his son was beaten to death during the massacres when Mnangagwa was state security minister. The killings were known as Gukurahundi.

Ngwenya says the president is not being sincere, and that, “He is blindfolding us to make us happy, yet we are not happy. … It’s painful, my child,” Ngwenya said.

“We want compensation,” he said. “If he cares about our cries and if the government cares about us and has sympathy, it must build me at least a two-bedroom house.”

According to Ngwenya, the army assaulted his son, Sibangani, who died along with eight others. Ngwenya says they were buried in a shallow grave about 5 kilometers from the family home three days later.

“I don’t usually come to this place,” he said. “I feel sorrow and pain since he died without falling sick. For the pain and sorrow to go, I have to be given something to console me, a two-bedroom house will console my spirit that yes, my son died. But my tears have been rubbed off,” he added.

“I want to have a place to mourn my son, not something edible as it goes away, but a permanent structure, something to stay in,” he said.

Nearly four decades after Zimbabwe’s independence in April 1980, access to water remains an issue in the southern African nation. Here women in the Tsholotsho district about 600 km southwest of Harare, April 18, 2019, spend time at a borehole to get water.

Gukurahundi debate

On the eve of Independence Day, the president said on state TV that citizens were now free to talk about Gukurahundi.

“The question of Gukurahundi, personally, I don’t see anything wrong debating it in newspapers, on television. Let’s debate it. We feared nothing about the debate. Actually, it’s critical that we have that debate. Some of the issues could’ve been resolved a long time back. … Gukurahundi has nothing to do with other people. It is an internal matter which has happened among us Zimbabweans, which we must discuss among ourselves,” he said.

Mbuso Fuzwayo, secretary of Ibhetshu Likazulu a rights group from Matebeleland region, in Tsholotsho district April 18, 2019, says President Emmerson Mnangagwa’s lifting a discussion and reburials ban of Gukurahundi massacre victims is not the end of the problem.

Only half of the issue

Rights organization Ibhetshu Likazulu has been vocal in calling for the Gukurahundi issue to be addressed. Its secretary, Mbuso Fuzwayo, says Mnangagwa has to deal with more than just allowing people to discuss the massacres and reburials openly.

“It is not those who are in mass or shallow graves who are going to be buried. Everyone will have peace when he knows where his father, daughter, son is lying. He (Mnangagwa) doesn’t talk about women who were raped. He is talking about half of what happened. Gukurahundi is complex,” he said.

Now it remains to be seen if the government has the will and funds to accommodate the people’s demands on Gukurahundi- VOA